Mapping the Social Lives of The Namibian Review

Mapping the Social Lives of The Namibian Review

Presented by

Archival Sources

Personal archives of the Abrahams family.Personal collections of Werner Hillebrecht, former Chief Archivist at the National Archives of Namibia.

Special Collections, University of Namibia Library.

Basler Afrika Bibliographien, Basel Switzerland

Journal Referenced

Last Updated

This tool is intermittently updated to integrate new information sent to the authors.

27 April 2022

The Namibian Review: A Journal of Contemporary South West African Affairs was published between 1976-1987. Initially it was produced by the Namibian Review Group (later known as the Swedish Namibian Association) and 14 editions were printed by Namibian political exiles in Sweden between 1976-1978. In 1979 the journal was translocated from Stockholm to Windhoek where another 18 editions were published in a context of intensifying southern African liberation struggle. For example, Kenneth and Ottilie Abrahams were the longest standing founding members of the Namibian Review Group, organized as an organization. They spent nine years in exile in Sweden, after escape from South Africa and South West Africa (colonial Namibia) to Zambia and then Tanzania after the infiltration of the Yu Chi Chan Club’s National Liberation Front, where all members were either incarcerated, killed, or escaped into exile.

The goal of the Namibian Review was to provide a platform for the discussion of all aspects of life in Namibia with particular emphasis on the problems of the long hard struggle towards independence. The journal encouraged a free flow of ideas “so that the leaders of tomorrow can prepare themselves, intellectually, for the tasks which will face them when they eventually take over the reins of power.” 1“Preface,” The Namibian Review Publication, No.1 “Three Essays on Namibian History by Neville Alexander,” June 1983, p.1. The journal was used as a place to campaign for democracy in its reporting on, analysis of, and arguments about the road to liberation, and the transition to independence.

▴ Kenneth Abrahams, “Editorial: Introducing the ‘Namibian Review’,” The Namibian Review: A Journal of Contemporary South West African Affairs, No.1 1976, p.2-3.

The publication came out over a decade of intensities of armed struggle in the present and fierce debates about forms of the postcolonial future. Each edition aimed to publish articles from a broad political, economic, cultural, social, and literary spectrum. Most editions included updates and analysis on the latest negotiation issues and politics. For example in 1978, the review carried articles on “Namibian on the Eve of Elections” by Ottilie Abrahams; “Prof. M. Kerina: An Interview by Kenneth Abrahams”; and “Current Events” by Nikodemus Muudjua. Often editions contained a range of race, class, and gender analysis. For example in No.1 Nov 1976 contained articles on “Appraisal of Turnhalle Economics,” “ Comments on Turnhalle: Women, Education, Culture,” and “Black Power, White Extremism, African Nationalism.” There would usually be articles both on the regional, national, and local front. For example in a double issue No.28 that came out in April/June 1983, there were articles on a range of issues entitled “the Internal Situation” from student movement mobilizing, from the Khomasdal Civic Association, the state of health care, local black business, etc. Articles were both informative, but also critical, including regular self-critique with the acknowledgement of failures, such as in an article No.17 (May/June 1980), an article on “a postmortum” on SWAPO-D (SWAPO-Democrats), a party the editors had been central to establishing after their expulsion from SWAPO, which they had also been central to establishing. In a similar vein, we find “A Critique of the ‘Kapuuo’ Edition, by D.S. and Others” and “A Reply” by Kenneth Abrahams (No.13, July 1978).

The Namibian Review’s editorial changed over time, partly due to the changes in the political context to which it was so intimately tied, and partly due to the changing structures of the journal itself, in terms of personnel but also the urgency of what it was responding to in the political moment, and how that shaped its agenda and form over time. We have identified what we think are five loose phases of the Review’s editorial structure. Writers involved in The Namibian Review included: Kenneth Abrahams, Ottilie Abrahams, Gabriel Tuhadeleni, Nikodemus Muundjua, Aaron Shindjoba, Elsa Brabant, Moses K. Katjiuongua, Paul Helmuth, Godfrey Gaoseb, Mbahimua Kapute, Hans Beukes, Z.A. Mnakapa, Timoteus Shilongo, Peter Shakumu, N.S. Haikali, Olavi Hamukuaya, T.M. Kanyamukulua, K.F. Lempp, David Hamadeni, Pio Marapi Teek, Andreas Shipanga, Issy Katjikuru, Fillemon Moongo, Gerhard Totemeyer, Jean Sutherland, Dorian Haarhoff, Max du Preez, Annemarie Heywood, Brigitta Lau, Olga Levinson, Lucky Shoopala, G. Holst, J.J.S. Alberts, Chris Saunders, David Simon, Joseph Diescho, D. Conradie, Yvette Abrahams, Peter Honey, Wolfgang Thomas, Neville Alexander, Keith Gottschalk, Tony Weaver.

You can peruse the front cover/table of contents of all editions we have been able to find below. Please get in touch if you have copies of edition numbers 7, 8, or 12, or have the cover page to No.26.

On Readership and Distribution. The Namibian Review published between 150-200 copies of each edition. The aim was to put out new editions every 3-4 months with a promise of a minimum of two editions each year (this sometimes resulted in double issues). From speaking to readers and finding pages of mailing address sticker labels, and reading letters of correspondence between the editors and readers from Zambia, USA, Germany, and beyond, we know that subscribers included: libraries, consulates, community groups, reading clubs, and individuals across Namibia, South Africa, Germany, USA, Finland. For example, organisational subscribers included: Black Student Study Project; the Hoover Institute on War Revolution and Peace at Stanford University; Dept of Human Rights in Wuppertal, West Germany; The Christian Aid Library in London; The Africa Institute in Pretoria; Blackwells, in Oxford; The Press Officer at the British Consulate in Cape Town; The Canadian Embassy in Pretoria; SACHED Trust, in Cape Town and in Johannesburg; AZAPO, Elsies River; New African, London; OAU Liberation Committee, Dar es Salaam; United Nations Library, NY; The Windhoek Archives, Windhoek; University of Dar es Salaam, The Library; NORAD, Lusaka. Our sense is that approximately 40-50% of the subscriptions were from libraries of states or universities, and various study groups, and about 20-30% from individuals.

Starting in 1983, the same team put out a new series, Namibian Review Publications, as “an extension of our work in this field… to give more coverage to work that came out of seminars held from time to time which focus on one single aspect of Namibian society, e.g. politics, history, education, agriculture or economics. Namibian Review Publications shall therefore reproduce, as far as this is possible, the lectures presented at these seminars, and each volume shall deal with one specific theme.” 2The Namibian Review Publication, No.1 “Three Essays on Namibian History,” June 1983 A total of six publications came out between 1983-1986. You can peruse the cover/table of contents pages of the Namibian Review Publications below. We are missing edition No.2, however a list of contents was published in The Namibian Review, No.30, (1983), p.2.

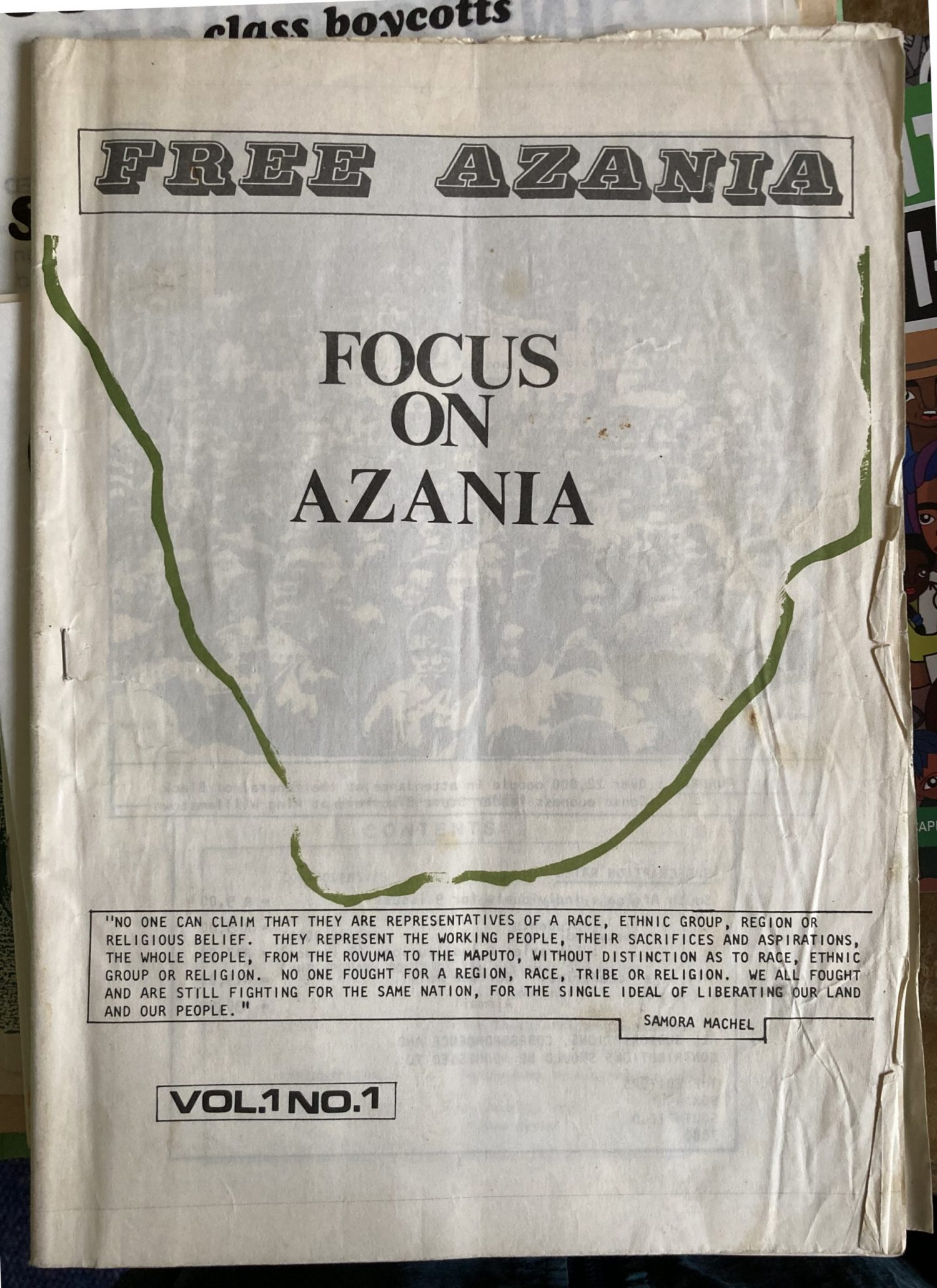

The Namibian Review was part of a constellation of publications that were part of the creation of movements and conversations between liberation movements across southern Africa. For example Kenneth Abrahams’s “State of the Nation” (Namibian Review No.32, May 1987) including a question of the role of NGOs was republished in Free Azania. For examples, articles about the establishment of the Namibian student movement and what liberating a curriculum would look like, written by Yvette Abrahams (Namibian Review No.28, 1981), who also spent her Sunday mornings as a child stapling the Review for mass mail outs, had parallels in The Namibian Student.

The Namibian Review was fiercely committed to the politics and practices of democratic debate, of education, of non-partisan politics which put liberation above any party and beyond any nationalism. It can thus be read both as history, as political debate, intervention, and invention with questions about the meaning and modes of work, at that time, and what it means for us today. In an editorial entitled “Reviewing the Review” in No. 17 May/June 1980: “we hope that Namibians will realise just how necessary it is for us to ‘invent’ ie analyse, suggest, and propose, ways and means to solve our problems, settle the independence dispute and create a better life for us and our children.” This was their political orientation to the national question, to the question of non sectarianism, to national fronts, and sole authenticity, representation, leadership, and education. The Namibian Review was in many ways an outlet and futurist impulse for critical pedagogy; this is one reason why we think that re-visiting this publication might be a way to resurrect critical pedagogy that proposes decolonial imaginaries. Without romanticizing The Namibian Review, we are interested in finding it, and studying it together, as both an education in history, organizing, and orientations to manifesting or putting into action radical thought produced in movement.

Mapping Movements: Living histories of radical study practices

The founding members, editors, organizers, and writers of The Namibian Review– Kenneth Abrahams, trained and working as a medical doctor, and Ottilie Abrahams, a committed teacher, principle, and feminist activist- were involved in the formation of anti-colonial liberation political parties, underground movements, in education work, in study groups, in writing position papers, newsletters, lectures, and strategic plans. In other words, The Namibian Review was just one piece in a much larger puzzle of the labours and movements for southern African liberation.

We first came across The Namibian Review in conversations with the late Ottilie Abrahams, who was part of the editorial team of The Namibian Review both in exile in Sweden and then when they relocated the journal back to South West Africa, as it was known at the time, in 1978 after two decades of lobbying for what became the passing of UN Security Council Resolution 435 (1978) on Namibia which called for the withdrawal of South African forces from South West Africa and for the transfer of power to the people of Namibia. We have been part of a small radical histories collective piecing together Aunty Tillie’s political life journey through militant underground reading groups in Cape Town in the 1960s, to exile in Zambia, to running the education camps in Tanzania, to splitting from SWAPO, to exile and lobbying work in Sweden, to establishing food security and education liberation schools in independent Namibia until her passing in 2018.

This work has been part of a creative approach to African history education that builds community across the colonial-imposed borders of the region. Our search for The Namibian Review, has been part of an active engagement in conversations about who holds these records of the past, and their various meanings. In reading the Review, we want to know what we (contemporary activists, historians & educators) can learn from these various intentional spaces/forms of debate, strategies, and knowledge production as we gather towards tomorrow, together.

In 2015, Koni and Asher began a series of interviews/conversations with people who had been involved in struggles against colonial apartheid in the past, and who remained involved in various ways, since 1994. These interviews were set up as conversations about what happened ‘then’, what they were involved in, and how they came to be involved; as well as about the demobilization period (what we understand the ‘democratic transition’ to be); and about how and why they chose to remain involved. We were trying to get at the question of how ‘now’ grew out of and might be similar and different from ‘then.’ These conversations, that we called Living Histories, also included or were often started or centered on discussion on student organizing now and various responses to that.

At the time, we were also involved in developing educational materials, we were designing and running Know Your Continent (KYC), a popular education series on African history. Some of the materials we used in KYC were developed by a team led by Neville Alexander in the 1980s while he was the Cape Town director of South African Committee for Higher (SACHED). We wanted to know more about the context of that work which had been developed for a number of different spaces -‐ for high school students in and out of school, for activists, for teachers and community discussion sessions; we understood this work to be important, urgent and radical both then and now. So it was through these conversations with people involved in various ways then, as well as through research for KYC, and for a section of a UCT course on histories of race and education, that we were exposed to many radical education initiatives and the important work of SACHED.

In 2016 we applied for a research residency grant for what we saw as “The Urgency of African History: History Education as Creative Practice.” We received support for a ten day research trip to collaborate with historians, artists, educators, and activists in Botswana and Namibia to workshop and explore historical themes, and produce artistic resources that respond to, and creatively depict the investigated histories. This was part of a vision to reimagine and pursue exciting, relevant practices of historical education with intention to connect, and build networks with historians, educators, activists and artists across the Southern African region. You can read more about this work, here.

The following year in 2017 we drew on these connections in planning the education programme for a Youth Without Borders Study Tour. This included Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja presenting on a post- Muafangejo approach to southern African resistance art, and a walk about at the Katutura Community Art Center and National Art Gallery; walking tours of Windhoek and sessions on histories of genocide and colonial land dispossession, early resistance, as well as liberation struggle history. One evening, Ottilie Abrahams came to speak to the group and share her history as a liberation fighter. While she did not want to be the focus of a biography she was keen for her students at Jakob Marengo Secondary School, to learn about the history of political organization and organizing that she was part of in the past, and continued to be committed to until her passing in late 2018. After a year of transcribing interviews, compiling texts and contexts, we returned in 2018 to present first drafts of the interactive mapping of her political life journey (below) with the students at her school, and at an arts festival: Operation Odalate Workshop at the Katutura Community Arts Center. In 2019 we extended this work with students at the school and students at the arts school, into murals, shared below.

This has been part of our approach to education/study as part of building cultures of resistance. Asher and Koni have written about this as a post-border praxis. We are interested in acknowledging and in creating spaces of learning together, ie classrooms, where we can collectively and creatively study politics in the interests of changing them. Our practice combines study, organizing, imagination, and creation. This is collective work. This is a praxis in process which we enact as part of a broader community through organising and education work with activists, artists, students, and educators across different spaces and borders in Cape Town, and South/ern Africa more broadly.

We are convinced that any relevant and radical politics of the future has to be based on a critical engagement with African history. It also has to be committed to a creative vision that imagines, a world beyond the multiple borders we have inherited, and engaged in a struggle to realise that future. This requires both urgent challenges to the political and geographic walls that control the divisions and distributions of commodified resources, such as land and citizenship, as well as an unpacking of how all borders are normalised, internalised, maintained and reproduced daily by and between people.

Our praxis beyond the classroom, which shapes, permeates and, in various ways emerges from the classroom and attempts to extend it, necessitates working across borders– in the city, the classroom, in the conceptual, historical, and the political. This work has been focused on trying to extend the classroom to create relationships, solidarity and community across various divides and distances to enable prefigurative enactments of post-border futures in the present. Through the dynamic movement between the classroom and the broader context that constitutes it, we try to nurture and encourage freedom’s dreams toward imagining a world beyond borders, thinking about what it will take to bring that world into being through collective action. Any possibility of what we imagine as a post-border world, requires unlearning and unpacking the historical baggage of borders, imagining and dreaming something different, creatively devising and planning how to get there, and struggling to realise it.

Below are two examples of experimenting with research, writing, and education as a form of organizing across borders, boundaries, and time.

Radical Histories I: SACHED and Some Others

We have pieced together a history of conservative and radical moves in South African education from 1949-2023, starting with imagining what history we will teach when the REC (Radical Education Collective – a continent-wide collective with cells of revolutionaries based at colleges, technikons, and universities) successfully takes control of the finances and the pedagogical projects of most of the higher education institutions in southern Africa….

Why? Because we are looking for histories of alternative education to support this future/present vision. These largely unknown histories are being used to inform the future educational agenda of the liberation movement which the revolutionary forces now have immense scope to shape.

But please note, this is an unfinished history of The South African Committee for Higher Education (SACHED) and some other alternative education initiatives under apartheid. It is unfinished in two ways:

- There is not a lot of existing writing on SACHED but many people hold and know the history because they were there. The piece’s unfinished character is an invitation to collectively help us all fill in some of the gaps.

- The other sense in which this piece is unfinished is that our history ends around the transition to neocolonial (in)dependence in the early 1990s. What happens to SACHED in that period is tied up with a broader narrative of demobilisation of progressive movements that took place across the spectrum – sports, arts, armed liberation forces, publishing, politics, community projects etc.

How were popular progressive movements like those mapped out here, which reached their height in the mid-late 1980s, then demobilised by/through/during the ‘democratic transition’? This is where we need to hear your stories on demobilisation/incorporation. Please get in touch, please add as we go. We have so far to go.

But for now, let’s cast our minds back and take another look at one of South Africa’s most significant alternative education projects/spaces…

The South African Committee for Higher Education (SACHED) was founded in 1959 by a group of academics, church people and educationists. It was established as a response to the 1959 Extension of Universities Act which segregated universities based on ‘ethnic’ identity and race. Some of SACHED’s foundational impulses were to mitigate against “ethnic education” and the associated stigma of inferiority, and to plug the gap of lack of Black tertiary educational opportunity since Black students could no longer study at the white universities.

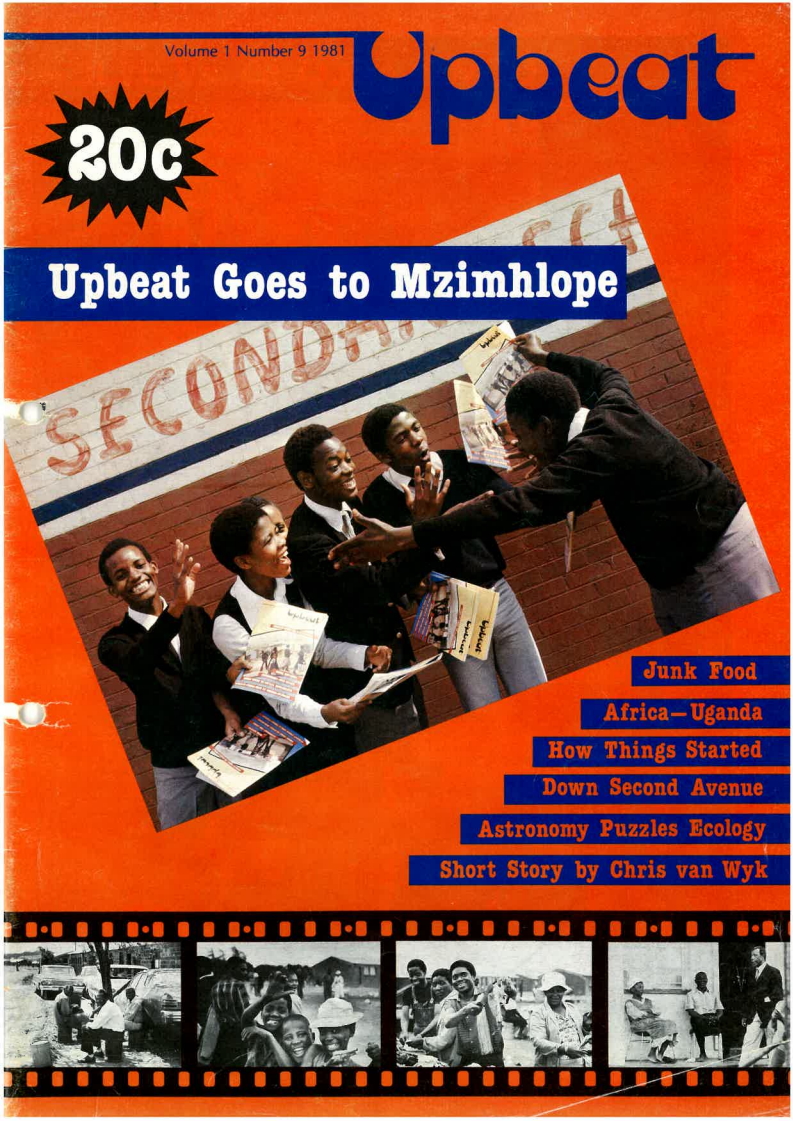

There was a wide range of political orientations and approaches taken under the SACHED banner at different historical moments from 1959 into the 1990s. By the 1980s, SACHED had 250 staff working in at least 9 cities and towns across South Africa. Not all, but many of SACHED’s initiatives were committed to establishing participatory, non-‐discriminatory and non-‐ authoritarian learning practices. Through conversations with people involved, through archival research and through secondary reading we have been researching SACHED and related projects which ran from 1960-1994 including: The Bursary Project (BP); Turret Correspondence College (TCC); Study Centers Project; The Bophuthatswana Teacher Upgrading Programme; a Newspapers Project; Labour and Community Programmes; UpBeat Magazine; Yu Chi Chan Club; SASO/BC Formation Schools; The History Workshop; Khanya College; Khanya Oral History Project; UWC People’s History Programme; Know Your Continent; National Education Crisis Committee and the People’s Education Movement; and Buchu Books.

It was interesting to learn about creative and flexible approaches to education which allowed them to respond to the ongoing crisis in education; with various people taking initiative and being given space, with relative autonomy and a minimum of bureaucracy, to use resources and to create projects and spaces of learning and building. We are interested in where this orientation to education work is now and what tactics/strategies/approaches from then remain important for us today. In this line, it seems important to think about how SACHED worked across so-called formal and informal spaces – doing educational work in schools, colleges, universities, community organizations and trade unions - and took on various publication and arts initiatives to produce and make available and accessible alternative resources to state-‐authorized education.

Ultimately, we wanted to know both about the range of projects but also about the political debates, which in some ways have fallen off the map of our timeline.

Conversations with people lead to reading articles and articles lead to speaking to people. We researched a time line, although we know that history is far from linear. And then it was time to narrow it all down, and select what to put in and what to leave out, this was difficult because there is so much. But we wanted to make space for what Paulo Freire calls the creative practice of reading. So while much more can and will be said or written, this timeline intentionally tries to make space for more to be written and heard by others and by us. In and between the details, the debates, and the what’s-‐nexts, many of the moments on this map are here as dots to spark conversations about the ongoing history of Radical Education Collectives. This can only happen in conversation with the future, and hence the ideas of writing in 2016 from an imagined future of 2024 and of leaving space-‐ as an imaginative invitation, for people to fill in what we are missing from then, and where these stories land now.

This timeline has therefore then been presented in various education spaces- from the Katatura Community Arts Center (KCAC) in Windhoek to the Neville Alexander Memorial Conference at the University of Johannesburg, where the history was first introduced in an interactive activity- radical history bingo- and then opened up for participants to add to the timeline that was up on the wall.

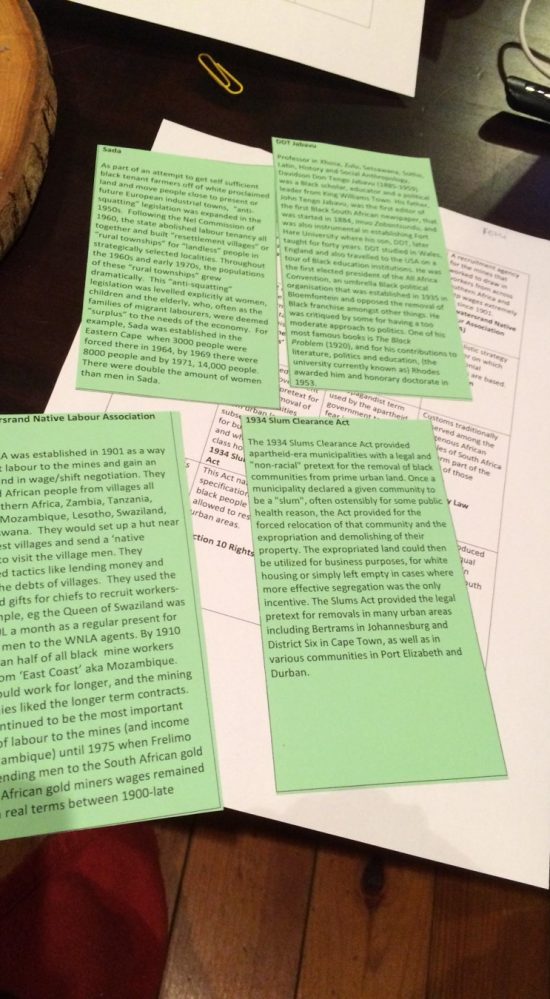

SACHED History Bingo

Radical History Bingo works like this: each participant gets randomly assigned a historical figure, process, organisation, event, place, etc. They get a paragraph describing this thing on a cue card and a bingo sheet with short descriptions and space for an answer in small squares. Each cue card is one answer to a question square on the bingo sheet. Everyone has to fill in all the squares by finding out information about each person’s clue. The first person to complete their bingo sheet wins. After someone finishes, the group collectively goes through each clue and has a discussion on each of them. The facilitators can prepare additional resources such as videos and/or music or other interesting materials which contribute to the discussion.

The facilitator needs:

- Introductory Notes, see instructions above.

- General Instructions for Playing Radical History Bingo, see instructions above.

- Printed cue cards- one for each person playing (if there are more than 16 people playing it is ok for more than one person to have the same card). PDF available here.

- A bingo sheet without the answers- one for each person playing. PDF available here.

- An answer sheet for the facilitator. PDF available here.

Radical Histories II: Mapping the Life Journey and Movements of Ottilie Abrahams

This interactive mapping activity is at once a history, a curriculum, and a work in progress.

The map below has two types of annotations: hover your cursor over the cards for a short text or click on a card to open a longer note.

Download a hi-res version of the map to print and play with here (file size, 6.9mb).

The facilitator needs:

- Introductory notes (optional!), to be drawn from the transcript of Ottilie Abrahams speaking to students, available here:

Koni Benson, Asher Gamedze, and Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja, “Radical Histories II: Ottilie Abrahams Speaks,” and “Mapping the Life Journey and Movements of Ottilie Abrahams: Revolutionary, Teacher Feminist,” in Owela: The Future of Work (Kaleni Kolletive, 2019) available at issuu.com/owela/docs/owela_publication. - Print out or draw a very large map of the continent of Africa. In the past, we have used an A2 print out, string, or flour poured on the ground. Be creative.

- Print out the narrator’s chronology: Marks on the Map, Facilitators Road Map. PDF available here.

- Cut out que cards and give one to each participant. PDF available here.

- Begin by giving participants 10-15 minutes to work in pairs on reading and studying their que cards and preparing to be ready to share the main points/most interesting parts of their card with the group, when it is their turn.

- The facilitator will then call out each milestone in Ottilie Abrahams political life journey and participants will come forward to read or tell the group about their card, and then decide where to place it in relation to the map of the continent. These choices make for interesting conversation. Likewise, the game often provokes interesting conversation, reflection, and sharing of ideas or experiences related to, and extending this history.

- Please take a photo of the final map and send it to us! Below is a gallery of some of the ways and places we have played this game.

Tigers Sports Club was founded in 1927 as the United Africa Tigers Football Club. Their men’s soccer team currently plays in the Namibian Premier League and the teams nicknames are ‘Ingweinyama’ and ‘Donkerhoek Boys.’ Their home ground is the Sam Nujoma Stadium in Katutura. Harry Boesak, who used to work with Ottilie Abrahams, wrote that while Ottilie was at high school “during the early 1950s, she was a member of the Young Tigers Sports Club in Windhoek, a club that was a front for reading and discussion. The ideological leaning of the club was towards the Pan-Africanism of Marcus Garvey, as espoused by Clemens Kapuuo inside the country at that juncture. In fact, the young former President Sam Nujoma participated in this club for a while.” The reading group was important for Tillie’s political and intellectual development. Boesak writes further that even after she moved to Cape Town, she maintained a connection with the club. “When Ottilie went to Trafalgar High School in Cape Town, her consciousness deepened there and she continued to provide literature from the Unity Movement and the South African Communist Party to the club.”

Land dispossession by Europeans began in 1883 when a German trader, Adolf Lüderitze obtained the first tracts of land from chief Joseph Fredericks in the south of what is now called Namibia. Germans began to exploit local conflict and sign treaties with indigenous rulers in return for protection. The trading of land grants had to be approved by the German Emperor. By 1893 practically the whole territory previously occupied by indigenous pastoralists, had been ‘acquired’ by 8 concession companies. Communal land use was replaced with private property ownership, and strict land boundaries. The Rinderpest epidemic that wiped out 90% of the cattle of pastoralists forced many people into wage labour and enabled colonizers to settle on the land they had ‘acquired’ on paper. By 1902 only 38% of the total land remained in black hands. The rest was controlled by concession companies, white settlers, and colonial administration. These unethical trading practices that resulted in this loss of land, spurred the indigenous wars of resistance in 1904.

1904/8 The Nama Herero Genocide

Ottilie Abrahams was a second generation survivor of the Nama Herero Genocide. This was the first genocide of the 20th century and a precursor to the Holocaust. In January 1904, the Herero people, led by Samuel Maharero and the Nama led by Captain Hendrik Witbooi rebelled against intensification of German colonial rule. In response, General Lothar von Trotha gave the explicit order to annihilate any Herero people found within ‘German territory’ whether armed or not. They were surrounded then driven into the desert where many died of dehydration or were killed in the retreat. Survivors were sent to extermination camps such as Shark Island. Between 25 000 and 100 000 Herero (50-75% of the population), and about 10 000 Nama people were murdered. With the closure of the concentration camps, all surviving Herero were ‘distributed’ as labourers for white settlers. All tribal and missionary lands were then expropriated and, uncultivated land tightly controlled. In 2011 the first 20 of the estimated 300 skulls stored in museums in Europe were returned to Namibia for burial. In 2015, Germany officially acknowledged the events a “genocide” and “part of a race war,” but has continued to refuse to consider reparations, despite ongoing law suits.

Jacob Marengo (1875-1907)

Jacob Marengo was the leader of more than 50 battles of resistance against Germans settlers between 1904-1908. He was best known for his ability to unite Nama and Herero rivals into his guerrilla army. His army, at various points, included Witboois, and some Xhosas and Namaquas from both sides of the Orange River. Born of a Herero mother and a Nama father, Marengo had a vision of broad African nationalism beyond ethnic loyalties. This is why so many revolutionaries liked his vision for the future of Africa. Nama-speaking people often refer to his love for humanity, and that he was the first leader to allow women to speak at council meetings. He employed guerrilla tactics and gained a reputation within the German army as a strategic genius and a noble fighter, earning him his nickname, “the Black Napoleon.” Marengo was eventually tracked down through cooperation between German troops and British police. Then he was shot and killed in a battle between his forces and a united German-British army, on September 20, 1907.

Trafalgar High School was established in Cape Town in District Six in 1912. It was a result of lobbying for schools for ‘non-Europeans’ by Dr Abdullah Abdurahman of the African Political Organization (APO) and by Harold Cressy. Cressy was the first ‘Coloured’ person to obtain a BA degree at the University of Cape Town. The schools, their educators and learners played a pivotal role in the anti-apartheid struggle. Leading teachers were involved in the Teachers League of South Africa and other political movements for liberation. During the 1970s District Six was declared a white group area and by 1982 over 60,000 people had been violently removed and relocated to the Cape Flats. There was fierce resistance against emptying the school to make way for white children. This resulted in the schools remaining open, despite having to commute from the Cape Flats, political repression, and other challenges. At Trafalgar Tillie was surrounded by fellow students and teachers who went on to become activist leaders in politics, in teaching, in music, in law, journalism, sport, and writing. Some people who attended the school include: Abdullah Ibrahim, Cissie Gool, Judge Siraj Desai; Alex La Guma; Sedick Isaacs Bennie and Helen Kies, Dullah Omar, Richard Rive, and Fatima Seedat.

The CPSU was established in the 1950s. It was affiliated to the Non European Unity Movement (NEUM) in South Africa. It aimed at overcoming racial divisions to forge unity and solidarity among students of different cultural backgrounds. In the 1950’s education had become one of the main terrains of struggle, due to the imposition of Bantu Education. Bantu Education attempted to submit all education to the ideology of apartheid – educating whites for privilege and Blacks for labour. University and high school students would engage in debates on issues from nationalism to armed struggle, liberation movement histories and political approaches to revolutionary struggle. It was at the CPSU that Tillie and Kenny first met people such as Neville Alexander, Dulcie September, Marcus Solomon and Fikile Bam – friends and comrades with whom they would work with in various formations and projects for the rest of their lives.

The original Society of Young Africa (SOYA) was formed in 1951 “as an intellectual vehicle to mobilise students at universities and high schools, as well as young workers. The slogan of SOYA – ‘We fight Ideas with Ideas’ – evidently reflected an organisation that emphasised the intellectual development of youth who would contribute to the struggle through debate.” It had its first conference in December 1951 and attracted a lot of ‘African’ students. It had a strong organisational presence in the Eastern Cape at universities, schools and in communities. SOYA branches worked with various peasant and worker organisations in their areas and participated in local struggles. SOYA was linked closely to the Non-European Unity Movement and it was led by IB Tabata. Tabata saw SOYA’s role as rethinking the role of ‘Non-Europeans’ in society. Their analysis of the situation was based on class exploitation and national oppression and they saw their role as educating people along those lines. Some key people associated with SOYA in the Cape were Phyllis Ntantala, Ottilie Abrahams, AC Jordan, and Dan Mokonye and Sobantu Mlonzi in Johannesburg. Another group called SOYA, Students of Young Azania, was started in the early 1980s around a similar time to Azanian Students Movement (AZASM).

Harry Boesak writes: “In 1953, Ottilie was a member of a student organization called the South West African Student Body (SWASB), which eventually became South West African Progressive Association (SWAPA). She acted as the deputy secretary general of these organizations and was the only woman in their leadership. She also raised funds for the further studies of young Namibians and to help start the first black newspaper, South West News.” SWASB was a group of students from South West Africa who were studying in South African (SA) universities. Many of them were radicalised by their experience of apartheid in SA as well as exposure to and involvement with resistance movements such as SOYA, ANC and others. SWASB became SWAPA, a political party founded by the same members, in 1955. Uatja Kaukuetu was elected as the first chairperson. SWAPA initially had very little presence and support outside of universities. In Windhoek, 27 September 1959, SWAPA united with Ovamboland People’s Congress (later OPO) to form SWANU (South West African National Union), an umbrella organisation to unite various movements. Later that year SWANU and OPO together were important in organising the December 1959 Old Location Uprising.

South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) & Ovamboland People’s Organization (OPO)

South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) is the current ruling party of Namibia which it has been since independence in 1990. SWAPO was an important, but not only, party in the Namibian liberation movement. It was founded in Windhoek on 19 April 1960, succeeding the Ovamboland People’s Organisation (OPO) which had been started in 1959, and Ovamboland People’s Congress (OPC) which was founded in Cape Town in 1957 by a group of people including Ottilie and Kenneth Abrahams, Andimba Toivo Ya Toivo and Andreas Shipanga. One of OPC’s aims was to end the exploitation of the contract labour system. Ottilie Abrahams was SWAPO’s first secretary of education in exile in Tanzania. She had many critical views of the party. “Ottilie believed that the sole and authentic representative status of SWAPO led to a suffocating and stifling political climate in the Namibian liberation movement and that as a consequence no democratic ethos existed in it.” Since independence many stories have emerged about the horrors of the SWAPO camps in exile, including the ‘dungeons.’ SWAPO has also told a narrow nationalist narrative of the liberation struggle which over-emphasises their role and silences and erases other historically important people and movements. Are the beautyful ones still not born?

Ottilie Abrahams grew up in the Old Location, where she lived until she moved to Cape Town to do standard 7 in 1951 at age 14. Her family was later moved to Khomasdal during forced removals of the 1960s. Old Location was on the western outskirts of the city, within walking distance to town. It had been growing since it was first established in 1912. In the 1950s, the municipality had put aside 1.2 million pounds for a plan to improve living conditions. At the same time the South African administration was working on the implementation of its Apartheid policies to segregate people into racialized group areas. Mixed neighbourhoods in towns were broken up and inhabitants resettled elsewhere. Local residents in Old Location protested and the police opened fire on crowds on 10 December 1959, killing 11 and wounding 44 others. This event is known as the Old Location uprising. The transfer of residents to the new suburb of Katatura, meaning “a place where we don’t want to stay,” took several years. In 1962, approximately 7,000 people had been moved. Eventually, most ‘coloured’ Namibians in Windhoek where settled in ‘Khomasdal’, five kilometres outside of Windhoek, divided by Katatura by a `buffer zone’ which was typical of apartheid racist social and geographical segregation. Until her death, Ottilie Abrahams stressed that the explosive urban housing issue was central to the land question.

The Namibian Review: A Journal of Contemporary Namibian Affairs was first published in 1976. Initially it was produced by the Namibian Review Group (known as the Swedish Namibian Association) and 14 editions were printed by the end of 1978. Each edition had articles from a broad a political, economic, cultural, social and literary spectrum. In 1979 the journal was moved from Stockholm to Windhoek. The goal was to provide a forum for the discussion of all aspects of life in Namibia with particular emphasis on the long hard struggle towards independence. The journal encouraged a free flow of ideas so that the leaders of tomorrow can prepare themselves, intellectually, for the tasks which will face them when they eventually take over power. The Namibian Review also tried to fosters a spirit of national unity – which Ottlie argued should transcend political party boundaries. Some of the articles by Ottilie Abrahams, included ‘Strategic Options in the Namibian Independence Dispute’ (Aug 1982), and “Present Political Groupings and Prospects for Coalition,” (Jan 1983). The journal was also used as a place to campaign for democracy, and publishing for example letters snuck out of the prison holes in Angola.

NAWA was formed in 1979 as the first women’s organisation that was not party political or a religious body, but an autonomous organisation of women for women. Beside all her educational projects, Ottilie Abrahams has been a stalwart of the women’s movement, speaking out on almost every issue and running NAWA. She represented NAWA in 1995 at the Fourth UN Conference on Women held in Beijing, China. NAWA built the Girl Child Movement and pushed for collaboration between organizations across the women’s movement. In a 2004 interview with Sister Namibia, Aunt Tilly explained: “I think women need to learn that when there are issues concerning women and children, and the development of the country is discussed, having a tidy house is not the most important thing on earth. If women came to a point and said ‘the future of our children and the status of women are the most important things for us,’ then we would really get somewhere, because once women commit themselves to a goal, they will be able to move mountains. Women must also stop insisting that they should always speak better English or have higher qualifications than men before accepting leadership positions. This country also belongs to us and we demand to play a full and equal role in its development!”

SWAPO-Democrats (SWAPO-D)

SWAPO-Democrats (SWAPO-D) were a breakaway group from SWAPO. In the mid-1970s Shipanga and some others had complained about the corruption and misuse of funds by the SWAPO executive. And they had called for a change in leadership. This incident is known as the ‘Shipanga Affair’ or the ‘Shipanga Rebellion’: For their ‘dissent’ Shipangas group was imprisoned by the party for two years without trial. SWAPO-D was founded in Sweden in 1978 after their release. It was a small group of ex-SWAPO members who believed in the party’s vision and principles but were critical of its undemocratic practices. Shipanga expelled both the Abrahams in 1980 on the grounds that they had “betrayed their positions of trust by indulging in acts prejudicial to the interests of the party.” In 1983 SWAPO-D joined the “South African supported Multi-Party Conference and in 1985 [went] into the so called Transitional Government of National Unity.” For these reasons SWAPO-D were seen by many as collaborators with the apartheid regime. Ottilie, SWAPO-D’s first Secretary-General, later said that “The formation of SWAPO-D was a mistake. But the feeling behind it was not a mistake. We did not want to leave SWAPO but we wanted the accent to be on democracy.”

When their underground cells were uncovered and Neville Alexander and Marcus Solomons were arrested, the Abrahams returned to South West Africa from SA. Together with other comrades, they established the Rehoboth branch of SWAPO. Hoping to melt into the background, Kenneth Abrahams began work as a doctor. Ottlie explains: “the Rehoboth Baster Council immediately declared my husband a citizen because I have a right to be a citizen, and he’s married to me. One morning about 10 trucks of soldiers came to arrest my husband…Those soldiers never reckoned with the people of Rehoboth, which was a semi autonomous ‘state’ where black people were allowed to own guns! There was actually a revolt, 400 people came with their guns and said ‘If you touch our doctor, blood will flow today!’ Oom Maans Beukes sent a telegram to the UN to ask them to intervene! It was very dramatic and the police were given the order to withdraw. But of course we knew that as soon as the people dispersed, they would come back for us.” Kenneth had to be snuck out of the country in the boot of a car, and Tilly had to travel separately from her babies, disguised as a young Herero girl who was expelled from Augustineum Secondary School for being pregnant.

In 1962 Kenneth Abrahams opened a medical practice in Rehoboth and was granted citizenship of the “Baster Gebied”. What did this mean? Basters make up the largest portion of Griqua people (people of European-slave, and European-Khoi, Khoi, San, and some BaSotho and BaTswana descent) who constituted their own community between the Cape Colony’s northwest frontier and the lower course of the Orange River at the end of the 1700s. With missionary influence, they developed written codes of regulation, many adopted from Khoi people – including the offices of the Chief, aka Kaptein, and Sub-Chief, Onderkaptein, that met at annual gatherings and developed their own constitution. They also elected Council – Raad members, responsible for the governing public life. In the 1870s Rehoboth Basters moved into an area south of Windhoek, where they joined a sub clan of the ǀGowanîn (Dune Damaras/ Damaras) who had settled in Rehoboth in the 16th century. The German colonial administration concluded a Treaty of Protection and Friendship with the Rehoboth Basters in 1885 where they recognized their right to self-governance. This self-governance was challenged and resisted in various ways over time, with ongoing calls for independence from the state of Namibia, and the return of ancestral lands.

After the failed attempt at arresting the Abrahams in Rehoboth, Kenneth hid in the mountains for a few days. Then he, Andreas Shipanga, Hermanus Beukes and Paul Smit had to march across the border into Botswana in August 1963. However, they were abducted – with a gun held to Abrahams’ head – inside Botswana by apartheid police in plain clothes, and taken to prison. This was at the same time that the escapees from the Rivonia Trial were also in hiding in Francistown- an environment Aunt Tilly describes as ‘electric.’ Kenneth was then flown to Cape Town and charged with sabotage. Following an international outcry, he was released and went into exile to Tanzania in 1963. The Abrahams met as members of the SWAPO Central Committee in Dar es Salaam to discuss a strategy for guerrilla warfare and to form the Peoples’ Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN). At this point Ottilie was the SWAPO secretary for Education. During a brief mission to Kenya in 1964, the Abrahams’ returned to Tanzania to find that they were suspended from SWAPO for ‘disrespecting leadership’ through enquiring about how funding was being used in the organisation.

After the democratic rebellion of the Shipanga faction in SWAPO, Abrahams and others formed SWAPO Democrats (SWAPO-D) in June 1978 in Stockholm. Their time in Sweden was a combination of a place to organize, to write, and to reflect. Ottilie Abrahams recalls the generosity and space granted to herself and her children in these years, and the appreciation of how they were treated as refugees. At the same time, there were serious debates about the hypocrisy of Nordic solidarity. The Swedes promoted democratic practices in their own pre-schools. But at the same time, following OAU Liberation Committee practice, they anti-democratically only funded and supported particular parties of the liberation movement. This created problems in the movement as a whole. Tillie asked: ‘Why a one party approach when it comes to Africa?’ “One day when I am old I want to write a book on the birth of the concept of sole authenticity. This is where it started. It is important, because it boosted certain organizations to such an extent that they became little Hitlers. Already in those years we fought SIDA (Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) and all those people, saying: ‘You are creating a problem for us which will cause the death of many, many people.”

The Abrahams spent five years in Zambia – where Ottilie taught at Kabulonga Girls in Lusaka, Chizongwe in Fort Jameson and then moved to the rural areas where she joined other teachers in opening a new school, Petauke Secondary School. Kenneth worked as a people’s doctor in Lusaka where he treated fighters from various national liberation movements in southern Africa. But their fortunes changed in 1968 – Ottilie was imprisoned in Lusaka following the infamous meeting between South African President Vorster and Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda, which led to attacks against political parties and the targeting of leaders of the liberation movement. “I was never told why I was arrested and eventually I was let out. With the help of a lawyer my husband was also released from Isoka prison and this time we found asylum in Sweden, where we lived for 9 years.”

The ‘End Conscription Campaign’ was a part of the Namibian independence struggle which reached its height in the 1980s. It was one of the many ways that people resisted the illegal military occupation of South West Africa (SWA). The apartheid government justified the occupation through propaganda that said SA was under ‘total onslaught’ and required a ‘total strategy’ military response. Namibian activists had been organising against South Africa’s illegal occupation for decades. One of the victories in that long battle was the UN Resolution 435. ‘End Conscription’ – the call to end white men’s compulsory conscription into the SADF (South African Defence Force) – was another part of the broader struggle against the apartheid governments’ military activities throughout the region – in Botswana, Namibia, inside South Africa and in other neighbouring countries. The campaign was supported internationally. Harry Boesak writes: “Ottilie and four others hastily returned from exile in 1978… In the same year, she was at the forefront of the end conscription campaign in South West Africa, and assisted in the production of pamphlets on the Photostat machine.” One of the campaign’s slogans was ‘NOWIN’ – no war in Namibia!

I.B. Tabata (1909-1990)

Isaac Bangani Tabata was one of the most important intellectuals in the South/ern African liberation movement and was a leading figure of the Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM), All African Convention (AAC), Anti-CAD (Anti-Coloured Affairs Department), and the African Peoples Democratic Union of Southern Africa (APDUSA). He was born in 1909 near Queenstown and passed away in Harare in 1990. Tabata was critical of the ANC and the CPSA (Communist Party of South Africa) and deeply committed to the rural struggles of peasants. He did a lot of work to connect the urban struggles to the rural – traveling and organising throughout the Transkei; publicising the NEUM’s Ten-Point Programme for revolution. His 1952 pamphlet Boycott as a weapon of struggle was translated into isiXhosa by teacher and writer Phyllis Ntantala. The Xhosa version, Ukwayo Isikrweqe nekhakha was widely distributed by SOYA activists in the Transkei. Tabata’s 1950 book The awakening of a people wanted to clarify “the real issues facing the Black masses of South Africa and serve as a guide to action.” And in 1959 he published Education for barbarism, an important and excellent analysis and critique of Bantu Education.

APDUSA is the African Peoples’ Democratic Union of Southern Africa which was established in March 1961 in Duncan Village, near East London.

While APDUSA had strong urban bases in the Cape, they were also focused on organising people who were living in the bantustans, one of the only movements to prioritise rural struggles. Many people who were involved in SOYA also became involved in APDUSA when APDUSA was established to replace SOYA. In 1962 Neville Alexander and Kenneth Abrahams were suspended from APDUSA over disagreements on the question of armed struggle.

The Children’s Movement (CM) was started in South Africa in 1983 to help children organise themselves into a community group based movement. By adopting the ‘Child to Child’ concept, the movement aims to empower children to change society from a ‘dog-eat dog’ society into a caring society. This was an initiative of Marcus Solomon, a fellow YCCC club member who at age 24 was sentenced to 15 years on Robben Island where, amongst other things he spent time reading philosophies of child psychology and its relationship to social change. The movement is based on the idea that adults must create the conditions for the growth of a united national children’s organisation and social movement for children and that children can teach other children whatever they need to know in order to change the world. Ottilie Abrahams explained the 5 principles: respect yourself, respect your neighbour, respect the environment, critical thinking, and participatory democracy. The current goal is to expand and to build an African Children’s Movement.

The newsletter of the CM also as a Revolutionary Papers Teaching Tool here.

In 1985 Ottilie Abrahams founded the Jacob Marengo Tutorial College, a school for liberation run on the principles of Paolo Freire, which she continued to manage as principal until two weeks before her death at age 80. Named after the leader of a Nama and Herero alliance against German colonists between 1904-1908, this school was founded in opposition to Bantu Education in Namibia. Aunt Tilly recalled: “When we started Jacob Marengo, a quarter of our students were from South Africa where schools were burned down–highly politicized children; and the other group came from northern Namibia, where the secondary schools had to operate under the watchful eyes of the occupying forces. So we saw our job as preparing children for an independent state, for the development of the country.” To actualize the school’s motto: ‘Education for Liberation’ they decided not to have a system of students representative councils. Instead, they had a system of self management groups called Turmas, where every child in the school has a specific task to perform. From 25 students in 1985, by 2016 the school last year had over 1000 children with about half the students come from Angola, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Education for Liberation was the motto of the Jacob Marengo School. It was a decisive shift of strategy from Liberation Before Education which was key to the schools boycotts and mass insurrection in the first half of the 1980s. The strategy of Education For Liberation used schools as a place of organizing and developing a vision, plans, and materials for People’s Education. The radical content, visions, and principles of the People’s Education movement were blunted when incorporated into the new Department of Education in South Africa in the 1990s.

In 1995 the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women held its fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, China. The previous conferences were in Mexico (1975), Denmark (1980) and Kenya (1985). The Beijing conference had 30 000 attendants from NGOs, movements and governments from all over the world. Among the goals of the conference was to “look at recent trends affecting the status of women, with an eye to the future. They will review how women have fared in the areas of health, education, employment, family life, politics and human rights.” Importantly, the conference made a renewed commitment to action fighting for women’s rights, education, and to eliminate “all forms of discrimination against women.” This was crystallised in the Beijing Platform for Action which was understood as “an agenda for women’s empowerment.” Ottilie Abrahams represented Namibian Women’s Association (NAWA) at the Beijing conference. In line with the commitments to action taken at the conference: “Upon her return from China, she started the Namibian Girl Child Movement (GCM), believing that decolonisation of the mind and freedom from mental slavery has to begin at an early age.”

Neville Alexander

Neville Alexander was a revolutionary and an intellectual with a deep commitment to education in the service of struggle. He was involved in many different organisations and movements throughout his life, including Yu Chi Chan Club, National Liberation Front, APDUSA, SACHED, and was an important figure in the drafting of the Azanian Manifesto. Neville was interested in, and wrote on African history, international histories of revolution, guerrilla warfare, multi-lingualism, the national question, and education. He studied for a PhD in Germany in the 1950s where he built relationships with German communists, trade unionists and learnt about the Algerian revolution. He did some historical work on Namibian anti-colonial struggles and wrote about Jacob Marengo and other important figures. He had close working relationships with Ottilie and Kenneth Abrahams, since the late 1950s in Cape Town. These relationships were important in setting up the connections between Jacob Marengo school in Windhoek and Khanya College. Khanya sent teachers to Jacob Marengo on recruitment missions and also encouraged graduates to teach there. Some of Neville’s important works are One Azania, One Nation which was written under the name NoSizwe, and his lesser known work on African history which he produced for the ‘Know Your Continent’ education series.

Yu Chi Chan Club

The Yu Chi Chan Club (YCCC) was a militant study group of nine members founded in Cape Town in 1962 by expelled members of the African People’s Democratic Union of South Africa (APDUSA): including Ottilie and Kenneth Abrahams, Dulcie September, Neville Alexander, Fikile Bam, Andreas Shipinga, Marcus Solomon, Xenophon Pitt. Amongst other things, the group studies and wrote on the politics and prospects of guerrilla warfare in South Africa at the time. Later in 1962 the YCCC was replaced by the National Liberation Front (NLF). After exile and imprisonments, YCCC members were central to SACHED’s education work in South Africa and Namibia in the 1980s.

National Liberation Front

The NLF was a revolutionary group founded in the early 1960s in Cape Town. Because of the repressive political climate, most of their activities were underground. NLF grew out of the Yu Chi Chan Club (Chinese for guerrilla warfare) – a militant study group also founded in Cape Town. YCCC saw their “primary task [as] to do ALL that is necessary to prepare for, plan and carry through the military phase of the Revolution in South Africa.” YCCC disbanded and NLF was launched in 1963. YCCC had nine members, some of whom had been expelled from APDUSA in 1961 over disagreements on the question of armed struggle. NLF was started as a political organisation to prepare for revolutionary armed struggle. The group studied revolutionary thought and history from around the world – Algeria, Cuba, Russia, China, etc. They wrote on the politics and prospects of guerrilla warfare in South Africa at the time. NLF understood South West Africa (now Namibia) as part of South Africa and they understood the liberation struggle as linked. They sent a comrade in 1963 to meet and build relationships with liberation movements and learn about the struggle in SWAPO at the time.

From 1920, after WWI, South-West Africa (now Namibia) was occupied and ruled by South Africa. Namibia achieved independence from South Africa in 1990. Part of the long struggle for independence involved, starting in the 1950s, putting pressure on the United Nations (UN) to force South Africa to withdraw and allow the Namibian people to determine their own political future. After over twenty years of sending petitions and delegations to the UN, finally Resolution 45 was passed. The UN Security Council Resolution 435 (1978) on Namibia goes as follows: “This Security Council resolution calls for the withdrawal of South African forces from Namibia and for the transfer of power to the people of Namibia. This resolution also establishes a United Nations Transition Assistance Group for a period of up to 12 months in order to ensure the independence of Namibia through free elections under the supervision and control of the United Nations.” This was an important step in Namibia’s independence struggle.

Otillie’s maiden surname was Schimming. The Schimming family is known for its anti-colonial and feminist activism both before and after independence. Otillie’s younger sister Norah Schimming-Chase was a member of SWAPO and later appointed as the Ambassador to Germany shortly after independence. Later, she joined parliament as part of the CoD political party where she played an important role of advocating for the rights of marginalized communities. Otillie and Norah were raised together with their siblings in a way that gender roles were challenged. Otillie’s daughter, Yvette who is also an activist and educator, studied her PhD on the resistance of Sarah Baartman. She heard her cousin Esi Schimming-Chase talking about Sarah Baartman and this prompted the struggle for return of her remains from Europe.

The Upington 26 was the largest group of people ever collectively charged for murder in a single South African trial. On 26 May 1989, “Justice J. Basson handed down death sentences on fourteen Blacks (Upington 14) for the murder of Lucas Tshenolo Sethwala, a Black police constable who fired at demonstrators attacking his home with stones on 13 November 1985. The rest of the twenty-five accused…received sentences ranging from six to eight years imprisonment and another six defendants were sentenced to community service.” The incident was framed by the government as part of the strategy to make the country ungovernable and the group was convicted on the basis of ‘common purpose’. The trial attracted international support for the prisoners, who had been sentenced for political reasons. In 1990 the death row sentences were overturned and in 1992 the Upington 26 were released in acknowledgement of them being political prisoners. Ottilie Abrahams said in an interview that some of the Upington 26 had been at school at Jacob Marengo. In May 2017 the Southern Africa Youth Network visited both Upington and Windhoek to learn about these histories.

Katutura Community Art Centre used to be a part of the larger old compound known as Okomboni or Ovambohostel where men from the north passed through before they were designated to their posts of contract labour. The building was constructed in 1970 by the South African administration. The original function of the main building where KCAC is currently housed was the kitchen and mass hall. These men were classified according to their physical strength and put to work for criminally low wages. They lived far away from their families and were easily abused and mistreated by their employees. Today, KCAC also hosts College of the Arts, several community arts initiatives and occasional workshops. For example, the youth without borders workshop in 2017 which Ottilie was a part of.

Youth Without Borders is an activist group based in Cape Town which has members from different parts of Africa including Zimbabwe, Congo, South Africa and Malawi. They envision a future Africa without borders, where African people are free to move, live and work wherever they choose. They organise against xenophobia and afrophobia in Cape Town and are involved in various youth educational and cultural programs with groups from different parts of the city. They are not just talking and thinking about youth, Cape Town, South Africa and Africa without borders, they are living it. Some of the members of Youth Without Borders were part of a Southern African Youth Study Exchange in May 2017 which went from Upington to Windhoek. The trip also included activists from across South Africa and a group from Botswana. The group learned about various struggle histories from Southern Africa. Ottilie Abrahams spoke to the whole study group when they were in Windhoek where she shared some history of some of the revolutionary movements she had been involved in. That speech is the basis of this history workshop.

Ayi Kwei Armah

In Sweden, Ottilie Abrahams finished her master’s degree and was writing a PhD thesis on the works of Ayi Kwei Armah, a writer from Ghana. Ayi Kwei Armah, was born in 1939 in Takoradi, Gold Coast, now Ghana. His novels deal with corruption and materialism in ‘post colonial’ Africa. He was educated in local mission schools in Ghana before going to the United States in 1959 to complete high school and then did a bachelors degree at Harvard University and a Master’s in Fine Arts at Columbia University. He worked as a scriptwriter, translator, and English teacher in France, Tanzania, Lesotho, Senegal, and the USA. Ottilie Abraham’s thesis focused on his first novel, The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born (1968). She was looking at the kinds of coups taking place across Africa immediately after independence and asking “if we all fought for independence why is it that people are regressing?” Studying Armah’s writing and drawing on her own experiences of cultures of democracy in political movements in her youth, she consolidated her thoughts on self reliance and participatory democracy which she implemented upon return to Namibia after exile.

In the 1920s, the South African government gained control of previous German ‘protectorate’ territories at the end of WWI. Then they appointed the Native Reserves Commission to report on land and labour. Their recommendation was that land be divided along racial lines. ‘Black Islands’ should be removed from what the Commission declared to be ‘essentially European areas.’ This paved the way for an accelerated program of settling mainly poor South African whites, as well as Angola Boer families on dispossessed Namibian land. Many OvaHerero pastoralists faced violent forced removals to marginal lands- including the maternal side of Ottilie Abraham’s family. Before 1914, the farms Fuirstenwalde and Aukeigas had been allocated to a Damara community by the German colonial government, and became known as the Aukeigas reserve. But in June 1956 the reserve was finally ‘deproclaimed’. 254 families (1,500 individuals in all) and thousands of livestock were forcibly re-moved to Soris-Soris in the arid north-western parts of the country. Aukeigas was then divided into two commercial farms and a resort – the present Daan Viljoen recreation resort.

The South African Committee for Higher Education was founded in 1959 by a group of academics, church people and educationists. It was established as a response to the 1959 Extension of Universities Act which segregated universities based on ‘ethnic’ identity and race. Some of SACHED’s foundational impulses were to mitigate against “ethnic education” and the associated stigma of inferiority, and to plug the gap of lack of Black tertiary educational opportunity since Black students could no longer study at the white universities. Some of SACHED’s projects included a bursary programs, the establishment of various colleges, curriculums, training materials, newspaper, labour, and community projects. In the 1980s, SACHED sent materials and teachers as well as funds for the initiation of the Jacob Marengo school in Windhoek.

In a 2004 interview with Sister Namibia, Ottilie Abrahams said that she views her own educational path and the establishment of the Namibian Girl Child Organization as the two major achievements of her life. She developed the Affirmative Action for the Girl Child Project in 1993, which she showcased at the NGO Forum at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995. Over a hundred girls from all parts of the country are now enrolled in this project, and every term holiday they come together for training in project development and leadership. Parallel to this came the establishment of the Namibian Girl Child Organization, which now has 186 girls’ clubs across the country. “The whole idea is to unite girls throughout Namibia, beyond tribalism and party politics, and to get girls involved in the solution of their own problems so that they don’t sit and wait for somebody to come and solve their problems for them. We are preparing for the launch of the African Girl Child Movement together with the SADC Girl Child Movement.” In 2000 the Girl Child Movement spread to South Africa, and it continues its activities in both countries. Since that time, they have expanded to include early training for boys in gender equality and set up the Children’s Resource Centre, again in collaboration with their South African partners.

The Abrahams returned from fifteen years of exile in 1978 after the passing of Resolution 435, and immediately formed the Namibian National Nationhood Programme. The motto of the program was: “We Liberate Ourselves.” They worked with various NGOs to support people to grow food and to provide education on methods of agro-ecology. Ottilie assisted in setting up four community gardens in the arid regions of Namibia (Wortel, Snyfontein, Abrahampos and Aroab) under the slogan ‘let us make the desert bloom’. She drove long distances to these projects, which aimed to tackle hunger and ‘restore dignity.’ As Aunt Tillie told us: We had formed different associations and organisations because we said ‘we can never wait for the South African government to do things for us, we will do it ourselves.’ They supported a number of projects based on participatory democracy where people determined the agenda and controlled the projects themselves.

The Abrahams spent five years in Zambia- where Ottilie taught at Kabulonga Girls in Lusaka, Chizongwe in Fort Jameson and then moved to the rural areas where she joined other teachers in opening a new school, Petauke Secondary School. Kenneth worked as a people’s doctor in Lusaka where he treated fighters from various national liberation movements in southern Africa. But their fortunes changed in 1968- Ottilie was imprisoned in Lusaka following the infamous meeting between South African President Vorster and Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda, which led to attacks against political parties and the targeting of leaders of the liberation movement.

After the a failed attempt at arresting the Abrahams in Rehoboth, Kenneth hid in the mountains for a few days. Then he, Andreas Shipanga, Hermanus Beukes and Paul Smit had to march across the border into Botswana in August 1963. However, they were abducted – with a gun held to Abrahams’ head – inside Botswana by apartheid police in plain clothes, and taken to prison. This was at the same time that the escapees from the Rivonia Trial were also in hiding in Francistown- an environment Aunt Tilly describes as ‘electric.’ Kenneth was then flown to Cape Town and charged with sabotage. Following an international outcry, he was released and went into exile to Tanzania in 1963. The Abrahams met as members of the SWAPO Central Committee in Dar es Salaam to discuss a strategy for guerrilla warfare and to form the Peoples’ Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN). At this point Ottilie was the SWAPO secretary for Education. During a brief mission to Kenya in 1964, the Abrahams’ returned to Tanzania to find that they were suspended from SWAPO for ‘disrespecting leadership’ through enquiring about how funding was being used in the organisation.

A video of Kenny and Ottilie Abrahams landing in Tanzania in 1963 to join Cabral, Frelimo, MPLA, etc. can be viewed in British Pathé’s archive here.

Black Power, White Extremism, African Nationalism

▴ Moses K. Katjioungua, “Black Power, White Extremism, African Nationalism,” The Namibian Review: A Journal of Contemporary South West African Affairs, No.1 (Nov 1976), 11.

The Social Responsibility of the Small Black Business Professional Men in Namibia

▴ Kenneth Abrahams, “The Social Responsibility of the Small Black Business Professional Men in Namibia” The Namibian Review: A Journal of Contemporary South West African Affairs, No.28 (Ap-June 1983), 33.

Ottilie Abrahams comments on Turnhalle: Women, Education, Culture

▴ Ottilie Abrahams, “Comments on Turnhalle: Women, Education, Culture,” The Namibian Review: A Journal of Contemporary South West African Affairs, No.1 (Nov 1976), 9-10.

Kenneth Abrahams: The Age of Pragmatism

▴ Kenneth Abrahams, "The Age of Pragmatism: A Comparison of the Economic Policies of Mugabe, Machel and SWAPO-D,” The Namibian Review: A Journal of Contemporary South West African Affairs, No.16 (April 1980), 16.

The Month in Review

▴ “The Month in Review- August/Sept/October,” The Namibian Review: A Journal of Contemporary South West African Affairs, No. 19 (Sept/Oct 1980), 24.

An Investigation into Socio-Economic Conditions in Khomasdal

▴ Holst and J.J. S Alberts, “An Investigation into Socio-Economic Conditions in Khomasdal” The Namibian Review: A Journal of Contemporary South West African Affairs, No.22, (April-June 1981), No.27 (Jan-Mar 1981), 16.

Letters of correspondence

Free Azania

Ottilie and Kenneth Abrahams

The founding members, editors, organizers, and writers of The Namibian Review, Kenneth Abrahams, trained and working as a medical doctor, and Ottile Abrahams, a committed teacher, principle, and feminist activist, were involved in the formation of anti-colonial liberation political parties, underground movements, in education work, in study groups, in writing position papers, newsletters, lectures, and strategic plans. In other words, The Namibian Review was just one piece in a much larger puzzle of the labours and movements for southern African liberation.

No. 1-5 (1976-1977): Editorial Board: Kenneth Abrahams (ed), Godfrey Goaseb (Asst. ed), Paul Helmuth (Treasurer), Moses K. Katjiuongua (sec), Ottilie Abrahams (asst. sec), Virimuje Mbuende (PR Officer); Published by the Namibian Review Group.

No. 6-15( 1977-1987): Editorial Board basically stays the same except Tillie and Moses swap roles and the Namibian Review Group dissolves (even though it is still listed as the publisher) and the Swedish-Namibian Association replaces it (both are listed on this issue).

No. 16 (1980): published by Dr Kenneth Abrahams (ed).

No. 17-30 (1980-: Kenneth Abrahams (ed), Ottilie Abrahams (sec/Ass editor), Jean Sutherland (res. Ass/editorial).

No. 31-32 (1984-1987): Kenneth Abrahams (ed), Ottilie Abrahams (assoc. ed).

Sticker Labels

Letter to the editors

Namibian Review Publications

Namibian Review Publications, no. 1 (June 1983)

Table of contents for Namibian Review Publications No. 2 (1983). The Namibian Review, No.30, (1983), p.2.

Namibian Review Publications, no. 3 (Oct 1984)

Namibian Review Publications, no. 4 (Feb 1985)

Namibian Review Publications, no. 5 (March 1985)

The Namibian Student

Koni Benson

kbenson@uwc.ac.za

Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja

jacquesmushaandja@gmail.com

Asher Gamedze

kingasher11@gmail.com

To invent

The Namibian Review, No. 17.

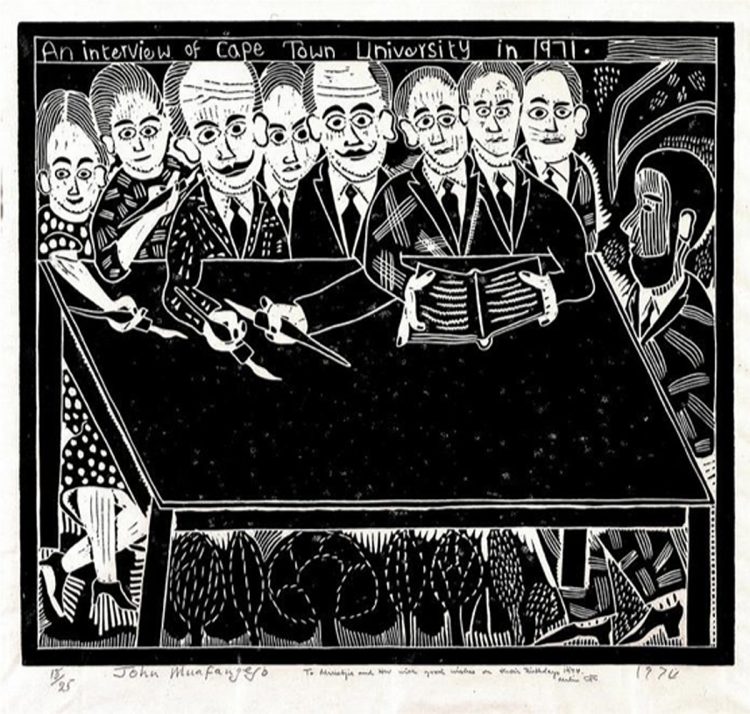

John Ndevasia Muafangejo

▴ An interview at the University of Cape Town (1971), John Muafangejo. Source: https://www.on-curating.org/issue-49-reader/editorial-1030.html

John Ndevasia Muafangejo was born in 1943 in Etunda lo Nghadi in southern Angola. He is Namibia’s most famous and world-renowned artist whose work has been and continues to be widely exhibited and celebrated. He was a printmaker who worked with the mediums of wood-cuts, lino-cut and etching as early as 1969. Muafangejo’s work touched widely on political, cultiural and religious issues, providing wide critical and creative commentary in the apartheid contexts of Namibia and South Africa. Following his arts education at Rorke’s Drift in Kwa Zulu Natal, Muafangejo’s work played a big role in enabling collective consciousness in the fight against colonialism and therefore forging black nationalism for southern Africa. This is often attributed to his experience as a colonized body but also his critical education from printmaking pioneers such as Azaria Mbatha.

After his studies, Muafangejo continued practicing art while working as an educator at St. Mary’s High School in Odibo, Ohangwena Region.

At the time of his death in 1987, Muafangejo had produced about 260 prints, many of which were included in many private and public collections in different corners of the world. It is argued that copyright of Muafangejo’s work which is owned by Europe-based Orde Levinson was acquired through dubious circumstances. This has necessitated the urgent need to restitute this work which Namibia is not benefiting from at the moment.

Some of the major exhibitions of Muafangejo’s works include Contemporary African Art Exhibition, Camden Arts Centre, London (1969), São Paulo Biennial (1972), Arts Centre, Durban (solo exhibition) (1975), Black South Africa: Graphic Art, Brooklyn Museum, New York (1976), John Muafangejo Graphic Art (solo exhibition), Bullankulma Art Gallery, Helsinki (1980), Black Art – John Muafangejo and Peter Clarke, IFA Gallery, Bonn (1987) and National Arts Festival, Grahamstown (retrospective) (1988). Apart from these exhibitions, Muafangejo’s prints have also been exhibited in several other group and solo exhibitions in recent years such as Labour of Love (2015).

Colonial Land Dispossession

Land alienation by Europeans began in 1883 when a German trader, Adolf Lüderitze obtained the first tracts of land from chief Joseph Fredericks in the south of what is now called Namibia. Germans began to exploit local conflict and sign treaties with indigenous rulers in return for protection against competitors. The German emperor declared that no trading of these land grants would be permitted with his permission. By 1893 practically the whole territory previously occupied by pastoralist communities, had been ‘acquired’ by 8 concession companies. Communal land utilization was replaced with private property ownership, and ridged land boundaries. The Rinderpest epidemic that wiped out 90% of the cattle of pastoralists forced many people into wage labour and enabled colonizers to settle on the land they had ‘acquired’ on paper. By 1902 only 38% of the total land remained in black hands. The rest was controlled by concession companies, white settlers, and colonial administration. These unscrupulous trading practices that resulted in this loss of land spurred the Herero and Nama war of resistance in 1904.