Al-Fatah and the Struggle for Press Freedom

Al-Fatah and the Struggle for Press Freedom

Presented by

Last Updated

This tool is intermittently updated to integrate new information sent to the authors.

10 May 2023

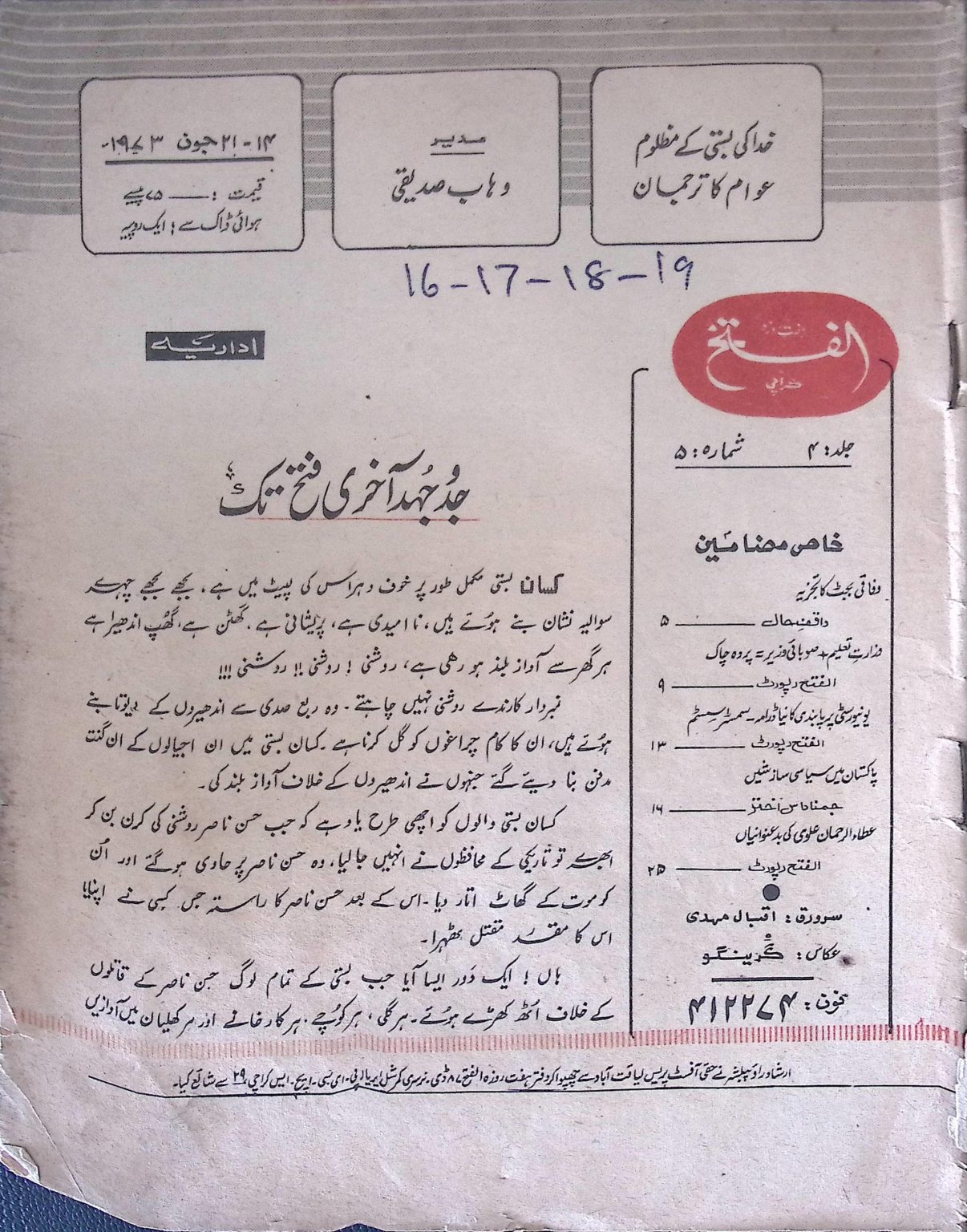

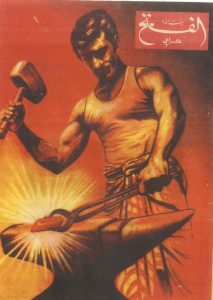

From the inside cover of the magazine. The Urdu text on top is the magazine’s slogan, which reads “Khuda ke mazloom awaam ka tarjuma” [The translation of God’s oppressed people]. Al-Fatah, 10 September 1979. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

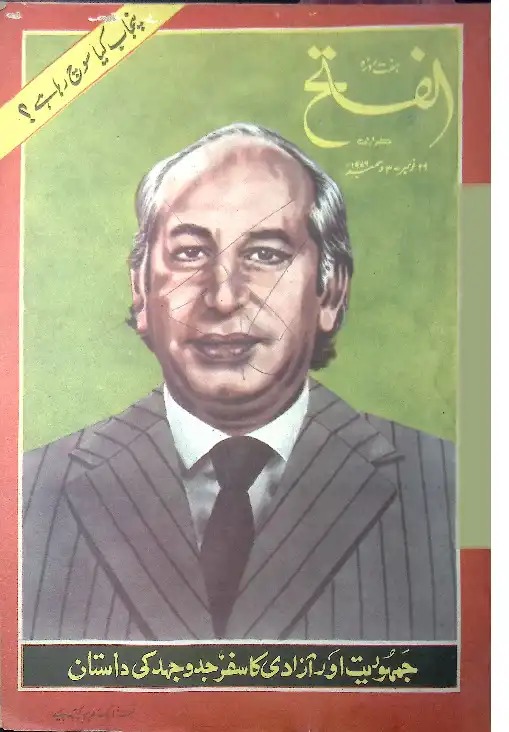

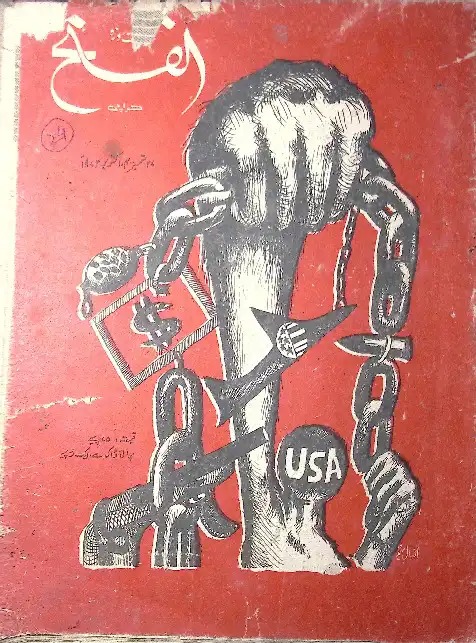

Al-Fatah (“The Victory” in Arabic) was a weekly Urdu-language socialist periodical published out of Karachi, Pakistan, from May 1970 till approximately July 1990. It published a wide variety of content, although there was a distinct proclivity towards political topics. Al-Fatah‘s socialist leanings informed many stances that it took during its run. It was decidedly pro-China and staunchly opposed oppressive imperialist powers like the United States and Israel. Furthermore, on a domestic level, it was rather critical of landlords and owners, and instead advocated for greater worker and union rights. Perhaps this proclivity is what allowed it to become a staunch supporter of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and his Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), which ultimately gained popular support for the same reasons.

This teaching tool aims to shed light on the team behind Al-Fatah while simultaneously tracing its involvement in press movements, in which both the publication and journalists associated with it became champions of press freedom. In doing so, figures such as Irshad Rao, Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi, Shaukat Siddiqui, Minhaj Barna, Hajra Mansoor and Wahab Siddiqui, while journalists by profession, found themselves shaping the very direction Pakistan would take in the tumultuous period which were the 1970s and 1980s.

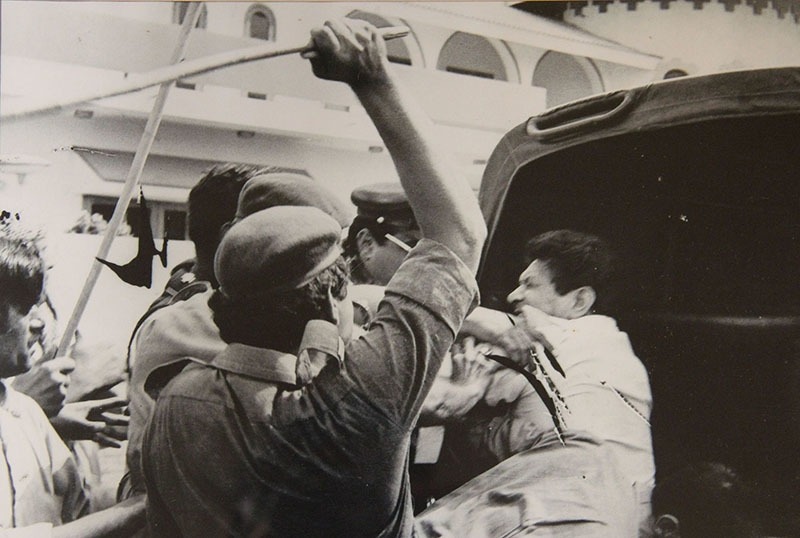

▴ Meraj Muhammad Khan, the president of the National Students Federation, being arrested during the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy in Karachi in 1983.

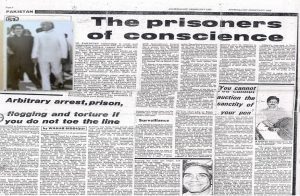

▴ The February 1982 issue of the magazine Journalist, in which Wahab Siddiqui wrote a piece denouncing the crackdown on Al-Fatah and its journalists.

▴ Zia addressing a White House State Ceremony in Washington in 1982.

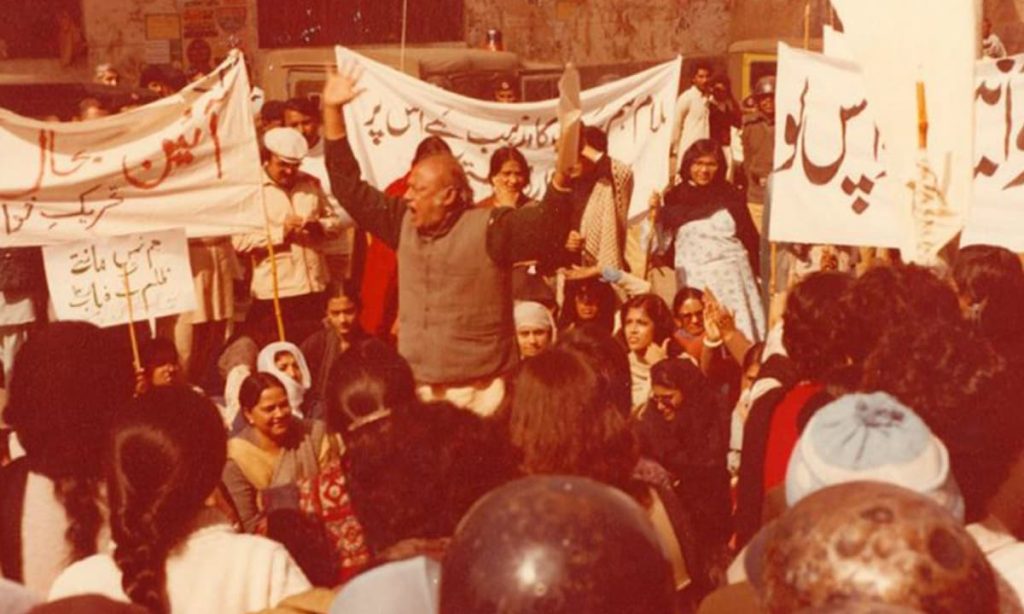

▴ Habib Jalib reciting a poem at a protest in Lahore, 1983.

Historical and Political Context

“The Middle East Now Calls for Palestine’s Freedom”. Al-Fatah finds itself sympathetic to the Palestinian cause. Al-Fatah, 25 February 1971 (Translation by authors). Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

Al-Fatah came into circulation during an especially volatile period as far as domestic and international politics go. It reported on the conflict between the East and West wings of Pakistan as the December 1970 elections drew closer, and the subsequent 1971 War between the two which led to the formation of Bangladesh. Being a pro-PPP publication, Al-Fatah naturally found itself taking the side of the western wing, albeit in a roundabout manner by suggesting, through its pieces, that the tensions between the two Pakistans were due to a concentrated effort on part of both India and the United States of America.

“The Constitutional Machinery Can’t Move Without the People’s Party”. Al-Fatah was supportive of the PPP. Al-Fatah, 25 February 1971. (Translation by authors). Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

In the first half of the 70s, Rao and his colleagues found many opportunities to demonstrate their socialist leanings. Being an inherently pro-China publication, Al-Fatah found itself adopting a pro-China stance on many international matters, such as Indo-China border tensions. Simultaneously, instances like the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 and the Vietnam War allowed it to address the dangers of US imperial powers which continued to destabilize regions worldwide for their personal gain.

“American Plot to Separate East Pakistan”. The divides being created between East and West Pakistan were largely attributed to US meddling. Al-Fatah, 25 February 1971. (Translation by authors). Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

When Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) came into power in 1971, it was felt that Pakistan would enjoy a degree of freedom that was stripped away by the military regimes of Ayub Khan (1958-1969) and Yahya Khan (1969-1971). While the former is credited with exceptional economic and agricultural reforms, he was also known for limiting press freedom and voices critical to his administration. For instance, he had used the Safety Act to arrest Sibte Hassan, the editor of Lail-o-Nahaar, for his criticism of the government 1Rahman, Ahfaz Ur. Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978). Oxford University Press, 2017.

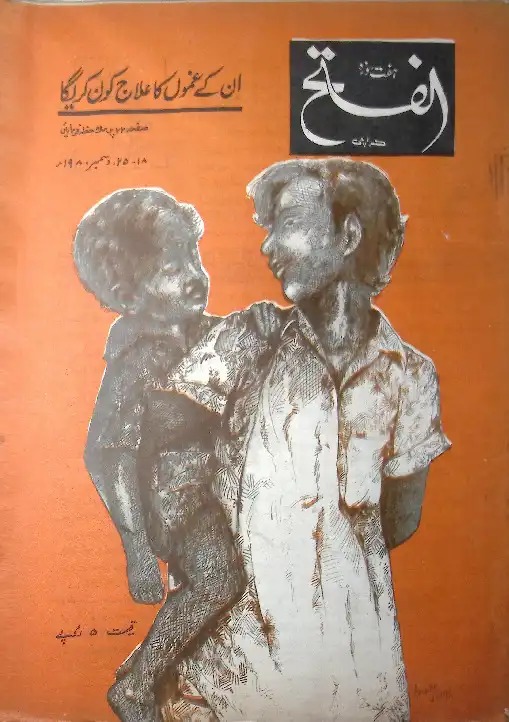

This was because Bhutto and the PPP had built themselves up in the public eye as champions of democracy, as well as the champions of workers and the poor through their socialist ideologies. To this end, their slogan was “Roti, Kapra, Makaan,” [Food, Clothing, Shelter] which were the basic amenities they promised to the struggling masses of the country. However, Bhutto’s rise to power came with its own unique set of problems. He was noted as having abandoned the politics of the poor with which he had gained popular support 1Rahman, Ahfaz Ur. Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978). Oxford University Press, 2017.. Rather than giving more rights to the workers, in line with his party’s socialist stance, he continued to deny them higher wages and further limited the power of labor unions. These policies, which ultimately alienated workers and unions, led to several instances of worker revolts like the one at Landi-Korangi and Kot Lakhpat in 1972 3Ahmed, Ishtiaq. “The Rise and Fall of the Left and the Maoist Movements in Pakistan.” India Quarterly 66, no. 3 (2010): 254–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45073152..

Al-Fatah was a pro-worker, pro-union publication. Al-Fatah, 1 June 1972. Source: Mansoor Raza.

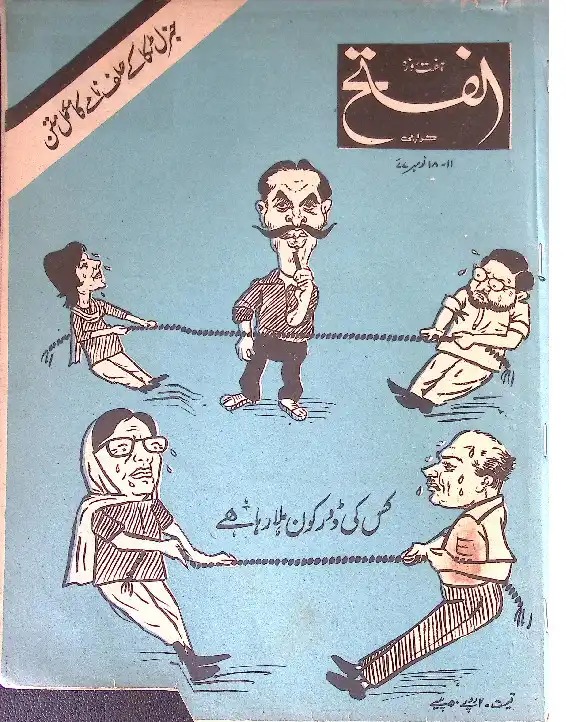

Furthermore, Bhutto’s nationalization of major industries gave him considerable power over employment and advertisement. By exploiting this, and ordinances like the Press and Publication Ordinance of 1963, he continued to silence critical voices in publications like Al-Fatah and Musawat, amongst others, by banning the magazines, jailing journalists or meddling with their revenue streams . In doing so, Bhutto started to appear very much like his predecessors – in certain aspects if not wholly. 1Rahman, Ahfaz Ur. Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978). Oxford University Press, 2017..

A newspaper clipping of Zia seizing power. Source: Dawn.

The political scene darkened further when Zia-ul-Haq came into power after establishing martial law once again. There are few figures in Pakistani history as polarizing as Zia, who was beloved by the Islamic Right and despised by the progressives and leftists. Under his regime, Pakistan underwent a process of Islamic radicalization, which saw secular elements in Pakistani society being overtaken by religious, Islamic ones. Simultaneously, voices of dissent were actively silenced – often through violent means. The Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) and its most critical members – as well as socialist activists who were presented as threats to Islam – were often targeted and jailed. Student unions and activists were also deemed a threat by virtue of their rebellious and disruptive qualities. The National Students Federation, which had played a pivotal role in protesting against Ayub Khan’s regime, also took on a similar role as a response to Zia’s draconian government. Its members were actively mobilized to protest against the government, such as the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (1983), which resulted in its leading members, such as Meraj Muhammad Khan, being arrested and jailed.

Meraj Muhammad Khan, the president of the National Students Federation, being arrested during the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy in Karachi in 1983. Source: Dawn.

“There will be no compromise on principles, Barna”. Minhaj Barna was associated with Al-Fatah and played a pivotal role in the Freedom of Press Movement of 1977-78. Al-Fatah, 28 April 1978. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

Numerous cases of torture and death were reported while these individuals were held captive. This became the spark for the Freedom of the Press Movement of 1977-78, to which Irshad Rao and Wahab Siddiqui were seen as pivotal. Both were eventually arrested for their opposition to Zia’s regime and its draconian practices. Subsequently, Al-Fatah was banned. However, it continued to be circulated to the masses, albeit under different names so as to evade authorities.

Throughout its run, Al-Fatah found itself in a political climate where critical, leftist voices were continuously silenced. However, its team – especially members like Rao and Siddiqui – would find themselves actively opposing these oppressive regimes and, in doing so, making a wider statement on the role and integrity of journalists in Pakistan. Apart from such journalists’ contributions in publications like Al-Fatah and Musawat, they continued to organize protests and pool together to pay fines that were imposed on them for their oppositional stance 5Since accounts were often blocked, journalists would pool together to pay the fines of their colleagues. These journalists would also go on hunger strikes which doubled as both a means to gather more support and to pressure Zia’s regime. The Karachi Press Club became one of the many sites nationwide where such protests actively took place, much to the authoritarian regime’s chagrin.

Journalists, including Al-Fatah editor Wahab Siddiqui, protesting through hunger-strikes Source: Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978), by Ahfaz Ur Rehman.

Al-Fatah’s role in this political climate was not a passive one by any means. It gave many critical individuals a platform to speak up against widespread injustices, whether they be the military dictatorship which Pakistanis were experiencing the horrors of domestically or whether they be the injustices faced internationally by groups such as the Palestinians or the Vietnamese. However, more so than existing as a mere weekly publication, Al-Fatah allowed for the organization and mobilization of a team of progressive journalists, often associated with organizations like the PFUJ, who zealously attempted to protect the sanctity of journalism in a regime which was actively engaged in the process of destroying it.

- Rahman, Ahfaz Ur. Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978). Oxford University Press, 2017.→

- Rahman, Ahfaz Ur. Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978). Oxford University Press, 2017.→

- Ahmed, Ishtiaq. “The Rise and Fall of the Left and the Maoist Movements in Pakistan.” India Quarterly 66, no. 3 (2010): 254–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45073152.→

- Rahman, Ahfaz Ur. Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978). Oxford University Press, 2017.→

- Since accounts were often blocked, journalists would pool together to pay the fines of their colleagues→

Key Figures

Irshad Rao – Chief Editor

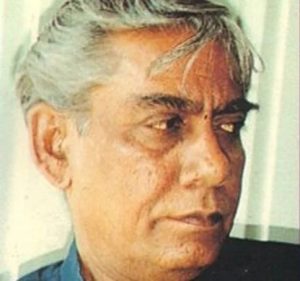

Irshad Rao. Source: Pakistan Press Foundation.

Irshad Rao was a prominent figure in the anti-dictatorship movement during Zia-ul-Haq’s military rule, and his contributions as a journalist were instrumental in mobilising the masses. As the founder and chief editor of Al-Fatah, Rao wielded his pen to challenge state oppression, campaigning for press freedoms and the rights of working journalists. In navigating the thorny landscape of censorship and repression, he became a beacon of hope for those involved in the struggle for democracy.

Rao used his platform to challenge military dictatorship, and bring attention to how it stifled the voices of Pakistani journalists. His work extended beyond print media since he was also a committed socialist, who took a pro-labor stance in his magazine. In one instance, he served as an arbitrator to resolve a dispute between labour and management at the Daily Tameer, in which he took the side of the workers 1“Subsequently, there were three courses of action available to the labor unions; firstly to go on strike, secondly to take the matter to the labor court, and thirdly to involve an arbitrator. The inexperienced labor unions never realizing the usefulness of the arbitration process used to tap the first two options more often. The arbitrator was supposed to hear the standpoint of both the parties i.e., management and the labor union, and then render a verdict just like an expedient labor court. However, arbitration is a modern progressive way of resolving issues, and this mechanism is rarely deployed in Pakistan even now.” Hashmi, Waqar Haider, and Riffat Bawa. “Labor Unionization in Pakistan – History & Trends.” Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies 2.2 (2010): 78-82..

Al-Fatah was driven by Rao’s revolutionary and socialist-democratic vision, which was closely aligned with the ideas of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and the Pakistan People’s Party. As a Marxist, Rao’s writing reflected the ideologies of Lenin and Mao, and his periodical was defined by its leftist perspectives on local, national, and regional socio-economic concerns. In promoting the PPP’s motto and platform before Bhutto came to power, and after his execution, Al-Fatah created a space for dissent, and added to the variety of perspectives on political issues. Moreover, Rao inspired a new generation of middle-class youth who were passionate about trade union activism, populist politics, and ideological stances. In the late 1960s and 1970s, these ideas played a central role in Pakistan’s struggle for social justice and democracy 2Raza, Mansoor. “A Red Revolution in Karachi for 50 Paisas a Week.” Samaa, 29 Apr. 2020, www.samaaenglish.tv/news/amp/2018742..

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto addressing a public rally. Source: Dawn.

During Zia-ul-Haq’s military regime, Al-Fatah saw some of the worst forms of suppression in the domain of media and journalism. It is during this time that Al-Fatah played a crucial role. Zia’s Revised Press and Publication Ordinance (RPPO) of 1980 led to torture, detention, and lashings for journalists, as well as the closure of numerous media outlets 3Hussain, Nazir. “Reassessing the Role of the Media in Pakistan.” Afficher La Page d’accueil Du Site, Feb. 2011, www.ifri.org/en/publications/editoriaux-de-lifri/lettre-centre-asie/reassessing-role-media-pakistan.. The state flouted democratic checks on its power, brutally suppressing the media, imposing strict censorship controls, and imprisoning journalists who tried to assert their independence. Irshad Rao and other senior journalists in the country made significant professional sacrifices during the Zia years, and their experiences made them fiercely protective of their freedom of expression.

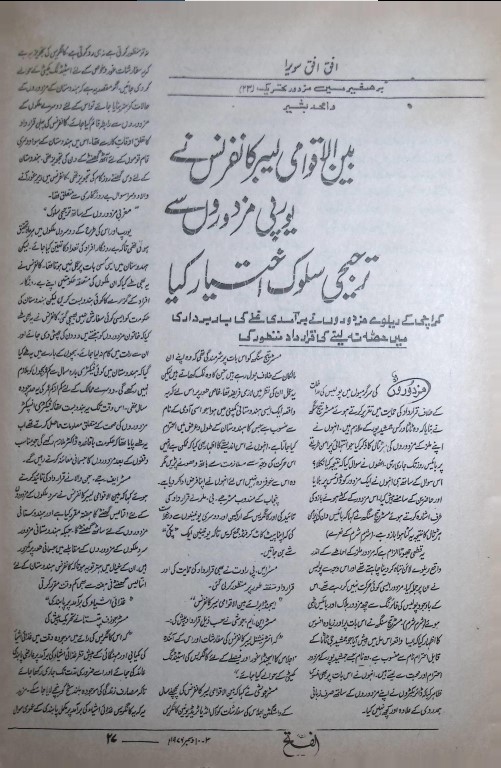

The February 1982 issue of the magazine Journalist, in which Wahab Siddiqui wrote a piece denouncing the crackdown on Al-Fatah and its journalists. Source: Hum Bhutto Hain on Facebook.

Under martial law, regulation 33 mandated a period of seven years of jail and 20 lashes if found indulging in “any political activity by words, signs or visible representation” Regulations were introduced that prohibited “dissent, criticism by word, action or gesture, and stifling all forms of expression” 4Farhad. “Curbing Free Thought.” Index on Censorship, vol. 14, no. 2, 1985, pp. 33–36.. This led to the targeting of individuals who possessed the means to mobilise opposition, such as by using their platform to articulate the discontent of the masses. Maliha Safiullah, the daughter of Irshad Rao, revealed that Al-Fatah was banned on nine occasions during General Zia’s rule. Yet, it managed to continue circulating under many different names, until Irshad Rao was apprehended and subjected to torture in a military cell 5“Veteran Journalist Irshad Rao Passes Away .” Pakistan Press Foundation, 16 Nov. 2022, www.pakistanpressfoundation.org/veteran-journalist-irshad-rao-passes-away/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=veteran-journalist-irshad-rao-passes-away..

Zia addressing a White House State Ceremony in Washington in 1982. Source: Dawn.

Irshad Rao was imprisoned and subjected to mistreatment for almost two years due to allegations of “printing objectionable literature, creating unrest among the masses and disaffection with the armed forces.” During this time, he was declared a Prisoner of Conscience by Amnesty International, and The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) also initiated a global campaign to secure his release. As a result of this outcry, some US Congress senators reportedly wanted to question Zia about Rao’s imprisonment, during one of his official visits to the US 6McGrory, Mary. “Zia Need Not Worry, He’s the Kind of General Reagan Likes.” The Washington Post, 7 Dec. 1982, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1982/12/07/zia-need-not-worry-hes-the-kind-of-general-reagan-likes/b7a2a8f3-98d7-42dd-a615-2f2de63db09a/..

Nusrat Bhutto leaves after speaking at a PPP rally in Karachi in 1978. Source: Dawn.

In 1981, Irshad Rao took upon himself to take Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s widow, Begum Nusrat Bhutto, to a meeting of opposition leaders where the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) was formed. Subsequently, he worked as the managing editor of the Daily Frontier Post. When Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s daughter Benazir became Prime Minister in 1993, she appointed him as her official spokesperson and then as an advisor on information in her first cabinet. Later, in 2007, he joined the National University of Science and Technology (NUST) as the Director of Publications. Rao passed away in November 2022 5“Veteran Journalist Irshad Rao Passes Away .” Pakistan Press Foundation, 16 Nov. 2022, www.pakistanpressfoundation.org/veteran-journalist-irshad-rao-passes-away/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=veteran-journalist-irshad-rao-passes-away..

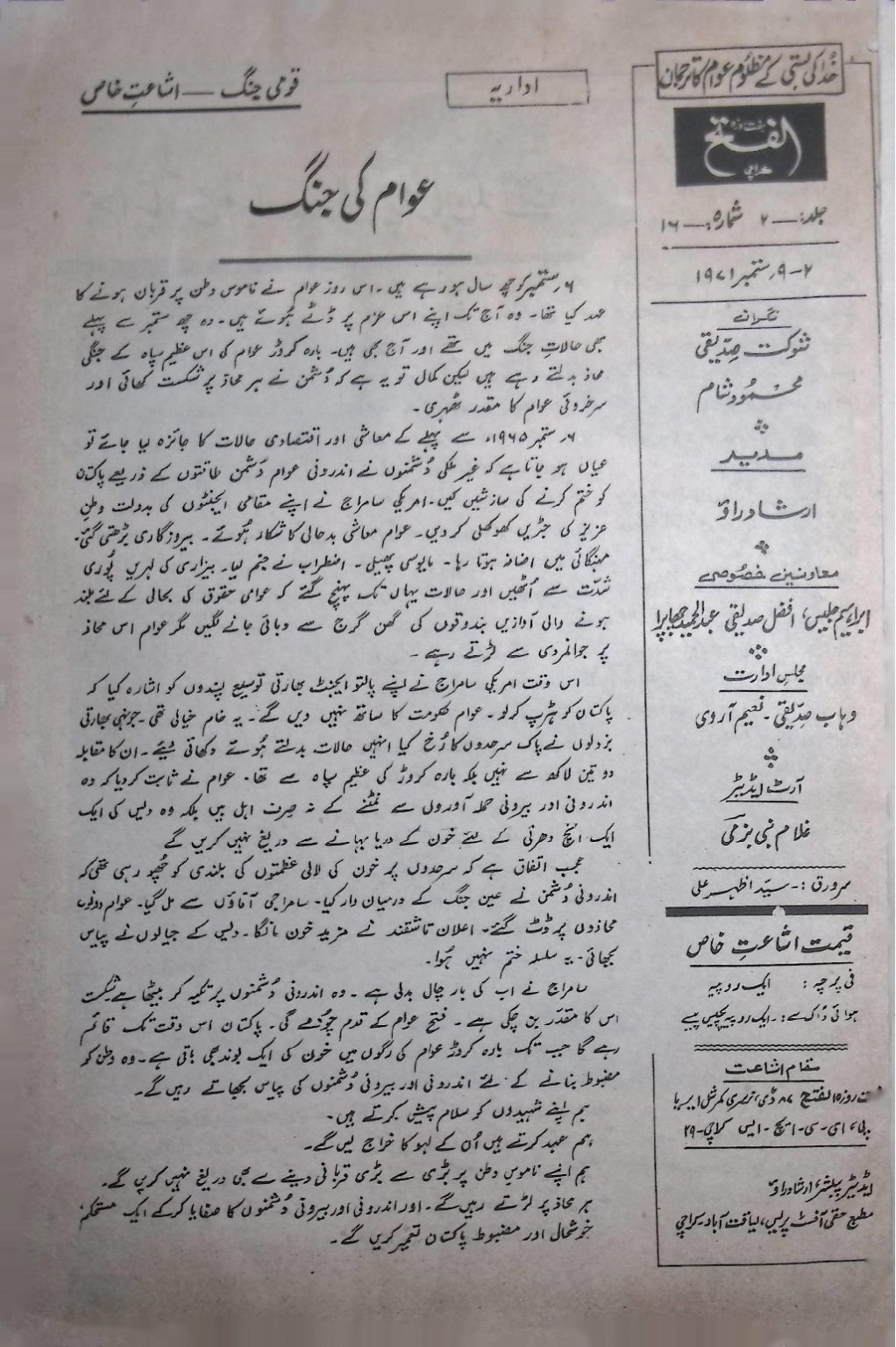

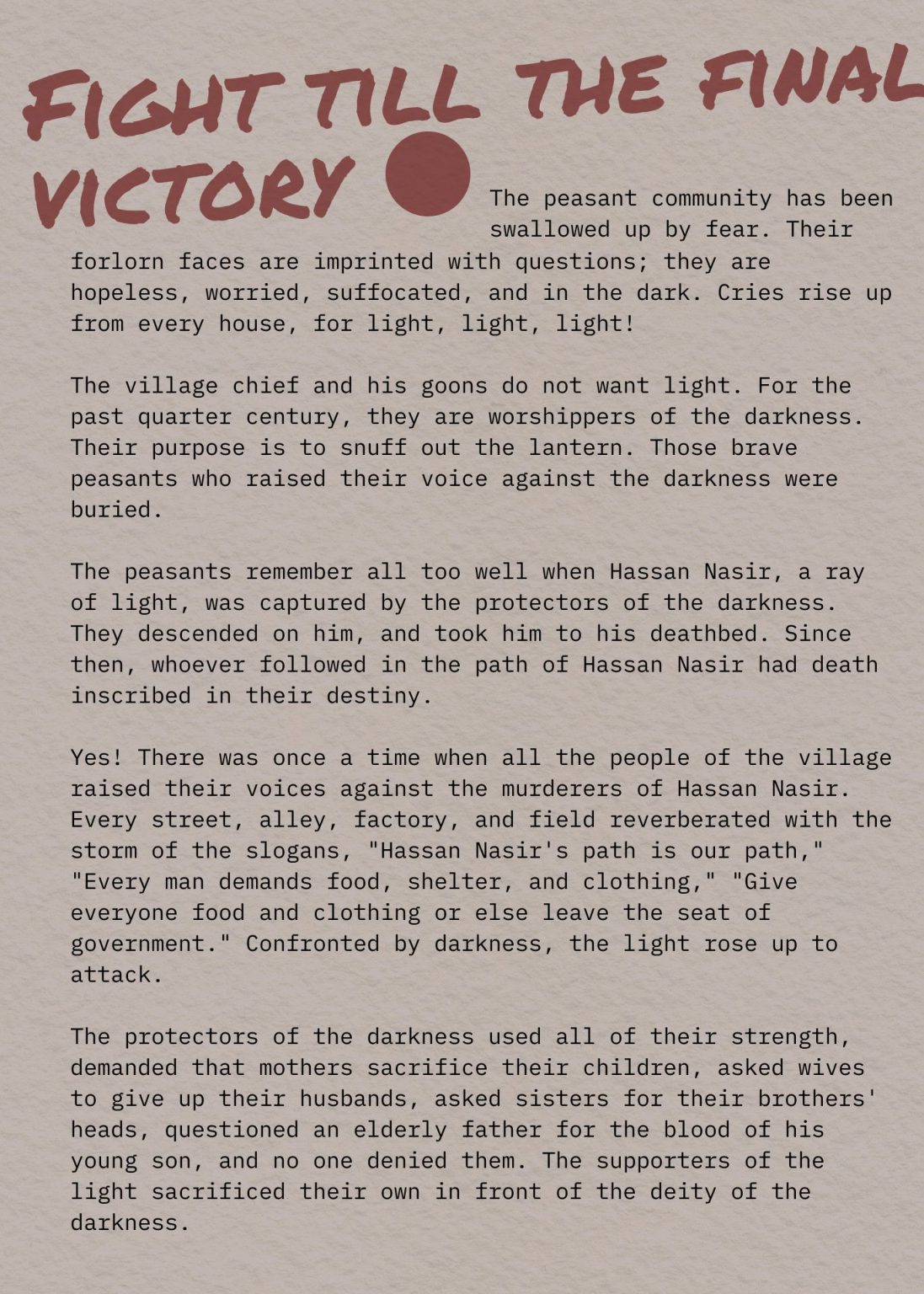

At the end of this section is an excerpt containing two editorials written by Irshad Rao: “Awaam ki Jang” [The People’s War] from the 2 September 1971 issue, and “Jidd o Jehad Aakhri Fatah Tak” [Fight Till the Final Victory] from the 6 January 1973 issue. The excerpt contains the original Urdu text (Source: SARRC, Islamabad) alongside their English translations (translation by authors).

Wahid Bashir – Staff Writer

Wahid Bashir Source: The News.

The magazine’s operations were held together by a closely-knit team of journalists and editors, of which one was Wahid Bashir. He was a versatile personality who was not only a poet, journalist, and trade union leader, but also a committed socialist who ventured in journalism with Al-Fatah, contributing a regular column about labour issues, called “Ufaq Ufaq Savera” [Dawn Rises]. Eventually, he also assumed the role of editor for several issues 8Salman, Peerzada. “Wahid Bashir Remembered.” Dawn, 28 June 2015, https://www.dawn.com/news/1190827..

When state suppression under Zia led to the brutal murder of Nazir Abbasi, a student leader and a member of the underground Communist Party of Pakistan, Rao led a movement against the regime through his magazine. To protest against Abbasi’s murder, Bashir and his colleagues from the magazine established an office. Bashir reached out to Begum Nusrat Bhutto, then Chairperson of the PPP, to request a statement condemning the murder of Nazir Abbasi. Consequently, Bhutto directed Bashir to write a statement which was composed by Sharif Ali, a well-known communist leader and a relative of Bashir. The statement was recited over the phone, Bhutto approved it, and it was broadcasted by the BBC. As a result of their activism, Sharaf Sahib, Irshad Rao, and Wahid Bashir were apprehended, and Al-Fatah was banned 9Hussain, Shahid. “In Memory of Wahid Bashir.” The News, 28 June 2015, https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/558922-in-memory-of-journalist-wahid-bashir..

Apart from his contributions to Al-Fatah, Bashir played a prominent role in the labour movements of 1963 and 1972. He was democratically elected as the president of the Karachi Union of Journalists, which reflected his standing within the profession. He also contributed to the editorial team of the Urdu-language magazine Irtiqa. He passed away in June 2015 10“A Great Loss: Wahid Bashir Passes Away.” The Express Tribune, 22 June 2015, https://tribune.com.pk/story/908024/a-great-loss-wahid-bashir-passes-away..

- “Subsequently, there were three courses of action available to the labor unions; firstly to go on strike, secondly to take the matter to the labor court, and thirdly to involve an arbitrator. The inexperienced labor unions never realizing the usefulness of the arbitration process used to tap the first two options more often. The arbitrator was supposed to hear the standpoint of both the parties i.e., management and the labor union, and then render a verdict just like an expedient labor court. However, arbitration is a modern progressive way of resolving issues, and this mechanism is rarely deployed in Pakistan even now.” Hashmi, Waqar Haider, and Riffat Bawa. “Labor Unionization in Pakistan – History & Trends.” Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies 2.2 (2010): 78-82.→

- Raza, Mansoor. “A Red Revolution in Karachi for 50 Paisas a Week.” Samaa, 29 Apr. 2020, www.samaaenglish.tv/news/amp/2018742.→

- Hussain, Nazir. “Reassessing the Role of the Media in Pakistan.” Afficher La Page d’accueil Du Site, Feb. 2011, www.ifri.org/en/publications/editoriaux-de-lifri/lettre-centre-asie/reassessing-role-media-pakistan.→

- Farhad. “Curbing Free Thought.” Index on Censorship, vol. 14, no. 2, 1985, pp. 33–36.→

- “Veteran Journalist Irshad Rao Passes Away .” Pakistan Press Foundation, 16 Nov. 2022, www.pakistanpressfoundation.org/veteran-journalist-irshad-rao-passes-away/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=veteran-journalist-irshad-rao-passes-away.→

- McGrory, Mary. “Zia Need Not Worry, He’s the Kind of General Reagan Likes.” The Washington Post, 7 Dec. 1982, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1982/12/07/zia-need-not-worry-hes-the-kind-of-general-reagan-likes/b7a2a8f3-98d7-42dd-a615-2f2de63db09a/.→

- “Veteran Journalist Irshad Rao Passes Away .” Pakistan Press Foundation, 16 Nov. 2022, www.pakistanpressfoundation.org/veteran-journalist-irshad-rao-passes-away/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=veteran-journalist-irshad-rao-passes-away.→

- Salman, Peerzada. “Wahid Bashir Remembered.” Dawn, 28 June 2015, https://www.dawn.com/news/1190827.→

- Hussain, Shahid. “In Memory of Wahid Bashir.” The News, 28 June 2015, https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/558922-in-memory-of-journalist-wahid-bashir.→

- “A Great Loss: Wahid Bashir Passes Away.” The Express Tribune, 22 June 2015, https://tribune.com.pk/story/908024/a-great-loss-wahid-bashir-passes-away.→

Irshad Rao’s Editorials

Censorship and Circulation under Zia

▴ A journalist being publicly flogged. Source: Dawn.

General Context

“A letter by Sabeeh Ud Din Ghousi from Jail”. Sabeeh Ud Din Ghousi was the Secretary of the Karachi Press Club. Al-Fatah, 2 June 1978. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

“3 June, When the Protesting Journalists Mark a Year of Resistance”. Al-Fatah, 9 June 1978. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

Censorship brought journalists, farmers, and students to the street. Censorship that made the act of starving oneself, an exertion of control and defiance. Censorship made press-freedom a war to be fought on several fronts. This was Zia-ul-Haq’s Pakistan. This was a journalist’s reality in 1977-88, and the conditions under which Al-Fatah circulated. In an interesting relationship, not only was Al-Fatah facing several manifestations of censorship, but it was simultaneously acting as the organizational force and mouthpiece for the Press Freedom Movement being orchestrated all over Pakistan.

What really gave the Press Freedom Movement momentum was the sheer unprecedented violence being undertaken by the State against journalists. Not only that, but this violence had a legal basis. In accordance with Martial Law Regulations No.49, the punishment for publishing any matter prejudicial to the integrity and security of Pakistan, morality and maintenance of public order, or against the purpose of Martial Law, was 10 years imprisonment or 25 lashes 1Aziz, Shaikh. “A leaf from history: four journalists flogged, two newspapers shut down.” Dawn. 13 May 2015.. For the first time in the history of the subcontinent, four journalists were flogged publicly. Telling the truth was now a crime.

With journalists being subjected to coercion, violence, and arrests- incidents of courted arrests in protest also increased. Around 168 journalists were arrested in Lahore. In response in Karachi, 300 press workers courted arrests 2Mahmod, Nazir. “Non-Fiction: When the press rose up for freedom.” Dawn. 8 April 2018. Al-Fatah acted as an organizational force in this mayhem. Ensuring the availability of counter-narratives to the state narrative, offering a small space where journalists could actually practice their craft: reporting on the truth.

Facing Censorship

Nonviolent Methods

The magazine faced censorship on many levels. First, there were instances of using bureaucratic red tape as a way of controlling the content published. This was a practice more common before Zia’s time, when PPP was in power. In 1971, all official advertisements for the magazine were stopped. In another instance, the newsprint quota was cancelled under the pretense that all the required documentations had not been submitted to the Audit Bureau of Circulation. Failure to do so meant no certification, resulting in no newsprint quota. Except the team had already submitted all the documentations and proof a year ago. Although the method of enforcing censorship did change with the shift in leadership, even Zia resorted to a variation of using government bodies to practice pre-publication censorship. In February 1980, after Al-Fatah was restored, a government official was assigned to go through the magazine before giving it the go-ahead for publication.

Brutality, Raids and Censorship

A list of volunteers arrested during the Freedom of Press Movement. Source: Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978), by Ahfaz Ur Rehman.

“Brutality Will Not Hinder the Journalist’s Protest”. Al-Fatah, 8 December 1978. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

A more common manifestation for censorship under Zia was one full of brutality, imprisonments, and incidents of violent raids. Intimidation was the main weapon, that could be wielded in an almost endless range of manifestations. The first representation of this was the firing of Minhaj Barna, the bureau chief of Pakistan Times as well as the president of PFUJ. The reason for his dismissal was his regular contributions for Al-Fatah. By 1978, the attack shifted onto the magazine itself. In April 1978, Wahab Siddique published an article regarding the worker massacre in Colony Textile Mills, Multan, the magazine was banned. Siddique was also imprisoned in Lahore.

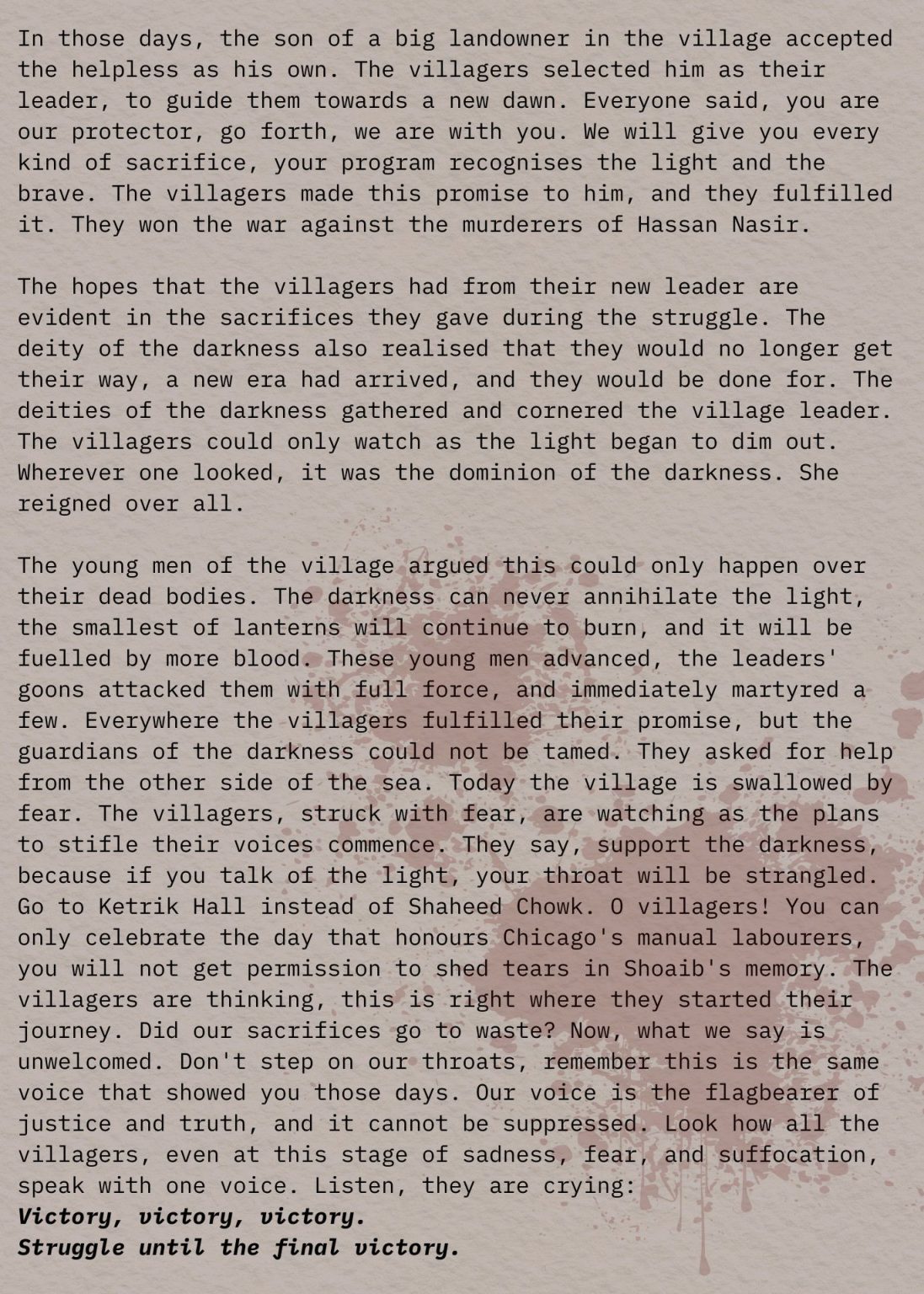

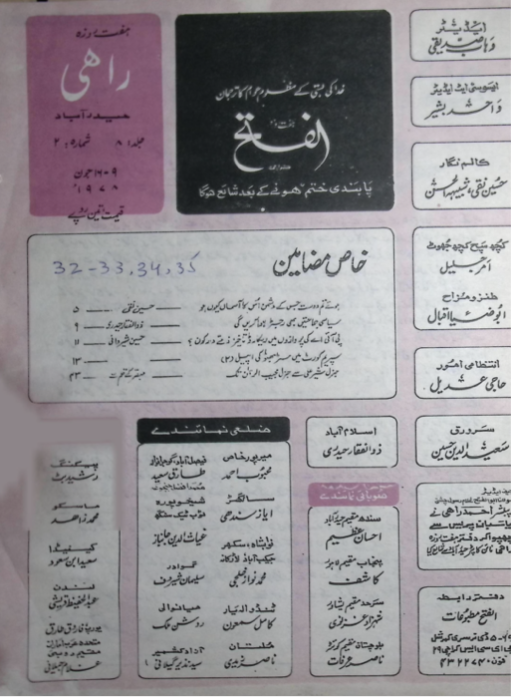

Here is where the resilience of the editorial team comes into focus. Despite the ban, the editor, Irshad Rao published Al-Fatah under 12 different the names and covers. These included Rahi, Zulfiqar, Parbhaat, Awaz and Inqilaab amongst others. These were all run by leftist revolutionaries and critics of Zia, such as the famed Urdu poet Fahmida Riaz, the founder of Awaz. Each time he came up with a new one, the State banned the last one. Within 15 months they were all shut down.

The State recognized the resilience behind the magazine and started using methods of coercion addressed not just towards the magazine as an independent body, but towards the individuals behind it. On 1st January 1981, an army major led a police raid on Al-Fatah’s office and Irshad Rao’s home. He was arrested and imprisoned for two and a half years 3Rahman, Ahfaz Ur. Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978). Oxford University Press, 2017..

Organising Against Censorship

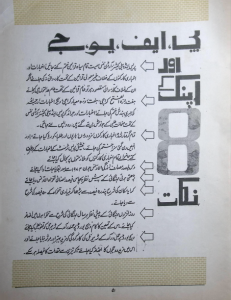

“PFUJ and APNEN’s 8 Points.” The second point articulates the Movement’s demand to unban the weekly Al-Fatah, weekly Mayyar and other banned newspapers and magazines. Al-Fatah, 8 December 1978. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

Despite facing the brunt of censorship, itself, Al-Fatah remained an integral piece in the Freedom of Press Movement. At a time, when the core exerts unquestionable authority over the intellectual production and physical conditions of Pakistan, Al-Fatah became a tool for the oppressed to organize themselves into an alternate core- resisting against the oppressor. Its primary purpose was to report on the sensitive information that was being erased. It covered the movement- articulated the demands, as well as published lists of arrested volunteers. In his work Freedom of The Press: The War on Words, Ahfaz Ur Rehman compiled a list from the material he could recover from the existing copies of Al-Fatah.

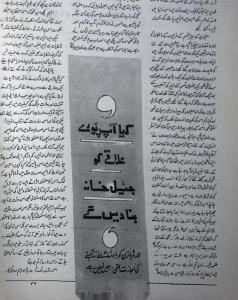

“‘Will you turn this entire area into a Jail?’ – Lord Byron had permission to question his ruler. We don’t”. Al-Fatah, 8 December 1978. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

In addition to that, it distributed information to workers all over Pakistan, news agencies and newspapers to ensure a dissemination of reality before it could be erased. In fact, the trigger for the movement was the ban of the magazine Musawat. The central action committees of the PFUJ (Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists) and APNEC (All Pakistan Newspapers Employees Confederation) met to start a movement against censorship. From that point, Al-Fatah has played the role of sharer of information 3Rahman, Ahfaz Ur. Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978). Oxford University Press, 2017.. In retrospect, the timely publishing of such significant events puts Al-Fatah not just in a position of engaging with the forces present, but also undertaking archival work of sorts.

At the end of the day, it came down to protecting the voice of resistance. That’s exactly what Al-Fatah did. Even when the activists had to succumb to state pressures, or were physically detained, their voices were carried on in the magazine. Letters from prominent leaders were published while they were incarcerated. This allowed the magazine to, in a way, perform the task of ensuring the momentum of the movement as well. It seemed to be saying: So, what if our leaders and our journalists get arrested? So, what if they beat us publicly? Threaten our families?

Nothing can contain the power of words, not even a prison cell.

- Aziz, Shaikh. “A leaf from history: four journalists flogged, two newspapers shut down.” Dawn. 13 May 2015.→

- Mahmod, Nazir. “Non-Fiction: When the press rose up for freedom.” Dawn. 8 April 2018→

- Rahman, Ahfaz Ur. Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978). Oxford University Press, 2017.→

- Rahman, Ahfaz Ur. Freedom of the Press: The War on Words (1977-1978). Oxford University Press, 2017.→

International Linkages

In many ways, Al-Fatah’s content was not only focused on national issues but also brought keen insight into its viewership of international events that were taking place across borders during its publication. In every magazine issue, the editors dedicated a section that shed light on either the politically charged environment of foreign lands or the foreign policy implications that Pakistan faced due to critical actors on the global forum.

June 1970 – American Imperialism Strikes Again

Cover page of the special Far East Asia Issue. Pictured here is Prince Sinahouk of Cambodia. Al-Fatah, 1 February 1973. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

The relationship between Far East Asian countries and the United States of America has been a tumultuous one. As an extension of the Vietnam War and the Cambodian Civil War, the Cambodian Campaign was conducted by the U.S. in 1970. In this article, American operations in Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Vietnam have been highlighted and condemned by the author who praises the resilience and defensive techniques of the Far East Asians who were able to successfully get rid of American forces in their lands. Overall, the article takes a negative approach towards the might of the American forces, which is described as a dog whose bark is worse than its bite. Even other national forces which were allied to the U.S. were not successful in their operations in the Far East Asian terrain which the natives were far more experienced in navigating. Due to this, it is not surprising that the native forces are gaining victories in driving out the Americans from their land.

Overall, Al-Fatah managed to convey not only the news of events which were taking place miles away but the articles were very well researched and in terms of the holistic picture, the American effort was assessed with harsh criticism. Al Fatah also expresses solidarity with the Far East Asians who were going through an ordeal which was even more brutal than the Britishers’ colonisation of the Indian subcontinent.

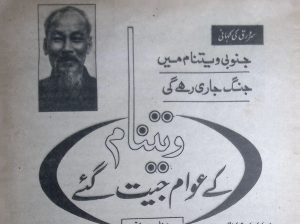

February 1973 – The Victory of the Vietnamese

“The Victory of the Vietnamese.” Al-Fatah, 1 February 1973. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

How often do weaker states defeat the might of strong, mighty states like that of the United States? Wahab Siddiqui paints a realistic picture of the painful ordeal that the Vietnamese have been through while not losing hope and determination in the face of adversity. Through their courage and solidarity, they were able to bring about the humiliating loss of American military operations in Vietnam. It is indeed a salute to the patriotic Vietnamese who saw the fruits of their struggle finally on 27 January 1973 when the agreement to end war efforts was signed. The agreement, signed by the Foreign Secretary of State William Rogers as well as multiple state officials of Vietnam, is an 8-page document stating the terms of ceasefire which included the immediate termination of oppression against the people of Vietnam and the release of war prisoners.

February 1973 – General Giap’s Military Tactics Force Imperialists Out

General Giap. Al-Fatah, 1 February 1973. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

After vacating the Indian subcontinent due to East India Company’s involvement, French colonialists targeted Vietnam as their next victim due to its geographical location and the abundance of natural resources. By 1883, due to their strength and advanced weaponry, they were able to gain some control over the Vietnamese but were unable to crush their spirit and their resolve to fight back their colonial masters. During this period, until the 1930s, Vietnamese retaliation did not bring any significant results due to fissures in the Vietnamese population between landowners and farmers as well as the colonisers and colonised. However, the working class had reached its limit of bearing suppression and post World War I, they turned towards Ho Chi Minh’s teaching. Heavily influenced by Marxism and Leninism, a proletariat revolution seemed to be the only solution to the Vietnam’s struggle, which led to the formation of the Vietnamese Communist Party on 3 February 1930. The reason why this was a welcoming change was due to the fact that the Party was able to connect the city dwellers to the farmers and peasantry under a single, strong banner. The unison under the Communist Party led to the realisation that success will come through armed struggle which can only be achieved via the People’s Army of Vietnam which vowed to free the country from the shackles of colonialism in December 1944.

Both the pieces have strong anti-colonial sentiments and are jubilant in the Vietnamese success. What is apparent is the encouragement of oppressed peoples to get rid of their colonisers using all and any means necessary. Al-Fatah, especially in this issue, has significantly expressed anti-American sentiments due to the actions of the giant state in relatively weaker states.

December 1973 – Pakistan’s Foreign Relations

“The declining influence of Britain and the rising influence of America on Pakistan.” Al-Fatah, 27 December 1973. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto meeting with the Chinese officials as Pak-China ties grow stronger. Al-Fatah, 27 December 1973. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

This article provides an extensive summary of Pakistan’s Foreign Relations with key international players. Starting off with France, the article praises French support in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and the United Nations Consortium in September 1965. Next, the cordial relations with Germany are discussed which have not been quite as beneficial for Pakistan, yet the hope still remains for better relations with the developed European country. Similarly, former colonial master, Great Britain, faces declining importance to Pakistan due to its neutral stance between Pakistan and India. Introspectively, the article advises patience and a polite attitude towards the mentioned countries in an effort to remain a team player.

On the other hand, the United State’s rise as a superpower and its consequent dethroning of the United Kingdom is mirrored in their relationships with Pakistan. The article makes a great effort to highlight the military and financial aid that the U.S. is capable of providing Pakistan in its time of need. However, it is also cautioning against the duality of U.S. interests to maintain Pakistani and Indian ties. Furthermore, the article also highlights the exceptional Pak-China ties that were gradually forming and shaping Pakistan’s near future.

Al-Fatah’s writers are quick to conclude that in the aftermath of the 1965 War against India, Pakistan has successfully learnt its lesson that diplomacy is the best foreign action in cases of conflict. More importantly, the article and overall tone of the issue reflected rationality in its approach to the foreign relation issues that Pakistan was facing.

May 1980 – Continued American Aggression in Iran is an Attack on Peace

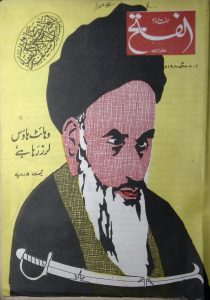

The White House is Defeated by Irani Islamic Revolutionaries. Illustrated here is Ruhollah Khomeini, the Shiite leader of Muslims in Iran. Al-Fatah, 1 May 1980. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

Nearly a quarter century ago, the CIA installed Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as the monarchical head of state. However, the Islamic Revolution in Iran finally brought his rule to an end despite the interventionist policies of the U.S. The new government knew better than to pander to American influences that were precisely the cause behind the Shah’s downfall and had led him to seek refuge in Panama and then Egypt on account of his health.

When a group of students learnt of the U.S. Embassy spying on Iran, they protested and eventually took over the Embassy and its delegates, who were offered their freedom in exchange of the Shah’s prompt return to Iran. In response, the U.S. took this attack personally and not only did it further its efforts to protect Shah Pahlavi, but also severed diplomatic, financial, and trading ties with Iran. Following in its footsteps, the European Economic Area (EEA) also gave Iran an ultimatum to do as told or face repercussions in the form of sanctions and trade embargoes.

In a bid to win the presidential elections, President Carter went on to launch missile attacks on Iran and endanger the entire region with turmoil and death. One failed mission led to the deaths of multiple American soldiers however this was still portrayed by the Carter administration as a success — a clear sign of imperialist mindset. Comparing the military intervention in Iran to that in Nicaragua and Vietnam, the author is positive that America will soon regret intervening in Iran’s political matters. The article ends in a dark tone that forces one to acknowledge how sovereignty, freedom, and democracy in other nations is of no importance to the U.S.

Arguably, Al-Fatah has published eye-opening details in its articles when it comes to key international events, something that the mainstream Pakistani media was bound to avoid. This can be deduced by the ample coverage of U.S. intervention in Vietnam or the uncovering of India’s meddling into Pakistan’s state affairs. Moreover, authors’ critical stances in their respective pieces is refreshing to see in terms of freeing the press, journalists, and inevitably, the people since it proves editorial freedom — a phenomenon which is rare in today’s media.

The rarity of the situation can be surmised by delving into Ali Raza’s article, “Dispatches from Havana”, which has analysed the importance of discourse against imperialism and oppression of subjugated peoples 1Raza, Ali. “Dispatches from Havana: The Cold War, Afro-Asian Solidarities, and Culture Wars in Pakistan.” Journal of World History, vol. 30, no. 1/2, 2019, pp. 223–46. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26675318.. For this purpose, in 1966, The Tricontinental Conference was held in Havana which brought together representatives from various revolutionary movements around the globe. The aim here was also to identify ways in which dialogue on such matters can be amicably and sustainably published. From a national perspective, in Pakistan specifically ever since the establishment of institutions such as Pakistan Academy of Letters and the National Book Foundation, it was apparent that all publications and cultural productions must be aligned with the state’s vision and how it is to be perceived 2Suhail, Adeem. “Saadia Toor: The State of Islam: Culture and Cold War Politics in Pakistan.” Dialectical Anthropology, vol. 38, no. 3, 2014, pp. 375–78. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43895109.. Al-Fatah is one magazine that has consistently strived to nurture a culture of open dialogue, transparent news and cross communication which is easily interpreted via the standard of journalistic values that it upholds.

- Raza, Ali. “Dispatches from Havana: The Cold War, Afro-Asian Solidarities, and Culture Wars in Pakistan.” Journal of World History, vol. 30, no. 1/2, 2019, pp. 223–46. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26675318.→

- Suhail, Adeem. “Saadia Toor: The State of Islam: Culture and Cold War Politics in Pakistan.” Dialectical Anthropology, vol. 38, no. 3, 2014, pp. 375–78. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43895109.→

Literary Content

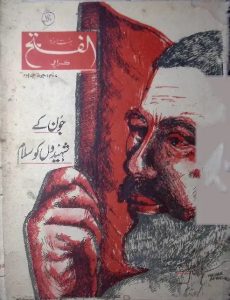

Habib Jalib reciting a poem at a protest in Lahore, 1983. Source: Dawn.

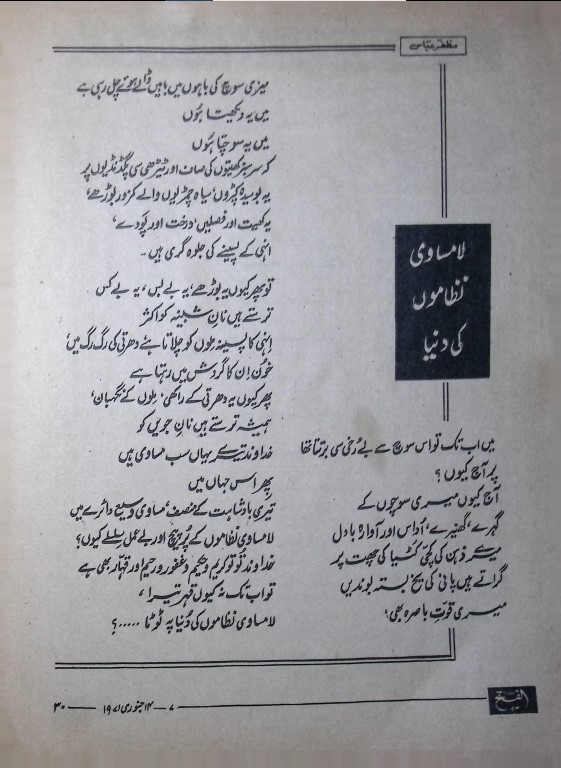

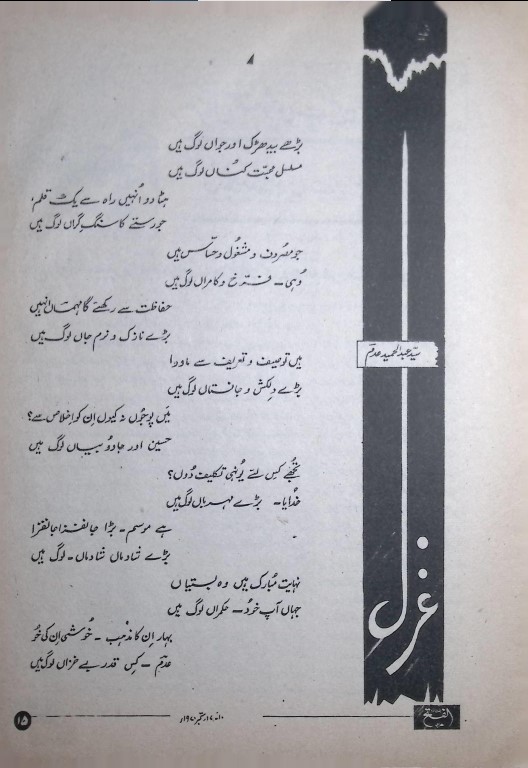

In keeping with the wider themes of the magazine, Al-Fatah also published a few literary pieces in each issue. These were usually poems – either the nazm (free verse) or the ghazal (rhyming couplets) – but as its print run progressed past 1975, the number of poems decreased in favour of short stories or afsanay. Some of the magazine’s regular literary contributors include Mahmood Shaam, Syed Abdul Hameed Adam, Farigh Bukhari, Nuqqash Kazmi, Makhdoom Munawar, Safdar Hamdani, and Khazin Ludhianwi. These figures had ingrained themselves into Pakistan’s journalistic or literary circles in the 70s and 80s, but the magazine also published works by some of the canonical poets, such as Habib Jalib and Faiz Ahmad Faiz.

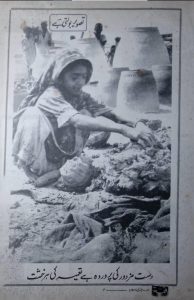

From a section called “Pictures that speak.” The caption reads, “The labourers’ hands nourish every brick that leads us to development.” Al-Fatah, 9 January 1976. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

In addition, the magazine received at least one contribution from Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi: a poem titled “In memory of the martyrs of September ‘65” in the issue published on the sixth anniversary of the 1965 India-Pakistan war. Qasmi was one of Al-Fatah’s patrons alongside Shaukat Siddiqui, and both were prominent members of the Progressive Writers Movement of the subcontinent. This movement largely sought to break with the Urdu-Hindi literary tradition, which it saw as overly-aestheticised and detached from the ground realities of the oppressed working class. Instead, it adopted the social realist style of writing, generally favoured the form of the short story over poetry and especially the ghazal (although there are numerous exceptions), and attempted to redefine the standards of literary aesthetics by finding beauty in the life and routine of the manual labourer.

Al-Fatah, 7 June 1973. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

In many ways, Al-Fatah carries on the tradition of the Progressive writers. The magazine is populated with poems that romanticise the hard work of the manual labourer, viscerally depict his struggle against hunger and oppression, call on the working class to pick up arms to fight for their freedom, and cry out against classist oppression in their demand for justice. The subject of these poems are usually the mazdoor (manual labourers), kisaan (farmers), public university students, prisoners, or army soldiers.

The image gallery below features two poems published in the magazine that focus on the plight of the working class, along with their English translations (translations by Munema Zahid).

Another notable contributor to Al-Fatah was Tariq Aziz, one of Pakistan’s most recognisable TV presenters. He was an avid supporter of the PPP, particularly remembered for firing up rallies and processions with “revolutionary slogans,” as well as a self-avowed socialist from back when he was in college. Aziz joined the PPP in March 1970, and was jailed for a few weeks at the end of the year, on charges of “truth-telling” according to Al-Fatah. In January 1971, he was released alongside Meraj Muhammad Khan, one of the founders of the PPP who would also later become president of the National Students Federation (NSF).

The 5 November 1970 issue (presumably around the time he was imprisoned) contains a scanned copy of a letter and a poem that Aziz wrote from jail. This is in addition to the many other pieces in the magazine penned by writers from jail, especially politically active students.

▴ A picture of Tariq Aziz, with his letter from jail. The letter reads, "Dear Shaam, my time here is passing by. Thank you for the copy of last week’s Al-Fatah, I greatly appreciate your kindness. A companion from Bahawalpur jail… [illegible] If you happen to like it, after making some minor corrections, feel free to include it in the magazine. Whatever time is left will also eventually pass. Meraj Muhammad Khan is busy making coffee, and he asks me to send his regards. From, Tariq Aziz." Al-Fatah, 5 November 1970. Source: SARRC, Islamabad.

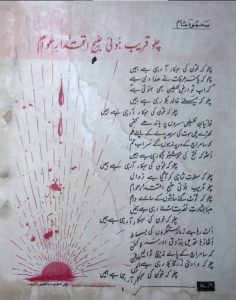

“Near is the morning of the people’s power,” a poem by Mahmood Shaam about the Palestinian liberation struggle. Al-Fatah, 1 October 1970.

Apart from poems that shed light on Pakistan’s working class, Al-Fatah also published literary pieces that showed support for socialist or anti-imperialist revolutions in other countries, and recognised key figures in these movements. For example, the magazine published two poems on Vietnam in early 1973, following the Paris Peace Accords, written by Saqi Javed and Rashid Mufti. In addition, Mahmood Shaam published a poem supporting the Palestine freedom struggle in 1970, a month after conflict broke out between the Jordanian army and Palestinian guerrilla fighters. Raees Amrohi contributed a poem on Sukarno, the Indonesian president, shortly after his death, and the Vietnamese revolutionary Ho Chi Minh was written about in two poems – one by Abdul Aziz Khalid, and the other by the eminent poet Habib Jalib (translated into English by Raza Naeem here).

Pablo Neruda on the Great Wall of China. Source: China Daily.

Moreover, the magazine also found its literary influences in writers from other locales. It published a translated poem by Pablo Neruda titled “Khooni Chowk” [Bloody Square] – one of his many poems about the Chinese people. In addition, it published an article on the life and works of Jean-Paul Sartre, reviewing his contributions to existential philosophy, as well as his preface of Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth.

“Greetings to you, the Leader of the Muslim Revolutionaries,” a poem by Farigh Bukhari about Imam Hussain. Al-Fatah, 7 February 1974.

A prominent trope that emerges across the poetry selection in Al-Fatah, which might also be an original feature of socialist literature produced in South Asia, is the metaphor of Karbala for the struggle against oppression. In the year 680, the grandson of the Muslim prophet Muhammad, Imam Hussain, was killed along with his family and supporters by the Umayyad caliph Yazid, at the site of Karbala in Iraq. The event has become a cornerstone in Islamic history, and Hussain emerges as a beacon of sacrifice, an exceptional figure who upheld righteousness in the face of evil. Many of Al-Fatah’s contributors have adopted the narrative of Karbala in their writings, using it as a metaphor for the raging injustice and oppression they saw in the country at the time.

Perhaps one of the magazine’s most illustrious literary features is a poem by Faiz Ahmed Faiz, published posthumously in the 7 July 1990 issue, titled “Khwab Basera” [Dream Abode]. Here is a link to its English translation, by Mustansir Dalvi.

The ghazal is a poem, usually untitled, made up of at least five rhyming couplets, with each couplet following a different theme. It is also the most common literary form featured in Al-Fatah by far, followed by the nazm and afsanay. In spite of the Progressives’ apparent distaste for the form, the ghazal was still favoured by many of the movement’s writers, and especially popularised by Faiz. As the modernist Urdu writer N. M. Rashid said, Faiz’s poetry “enables the timeworn cliches of the Persian and Urdu ghazal to acquire a renewed sensitivity and to be recharged with meaning, so that the solitary suffering of the disappointed romantic lover is transformed into the suffering of humanity at large” 1Mir, Ali Husain and Raza Mir, Anthems of Resistance: A Celebration of Progressive Urdu Poetry. Roli Books Private Limited, 2006..

Below is a video of Faiz reading his poem at his last televised mushaira (a gathering for reciting poetry).

In this poem, Faiz’s disillusioned tone embodies the broader sense of despair that was settling into the country forty years after the Partition of the subcontinent. From the death of the country’s founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah a year after Partition, till the tumultuous rule of Zia-ul-Haq, the country’s political climate had perhaps never truly settled. It was increasingly dawning upon people that the Pakistani state may have failed to live up to the promises made to them at the time of the Partition – and Faiz was only too aware of this, having been imprisoned in 1951 for a government conspiracy, and eventually retiring to Beirut in self-exile after Bhutto’s execution. He returned only two years before his death, which is when he is reported to have penned “Khwab Basera”.

Al-Fatah, too, is thought to have stopped publishing in 1990, leaving behind a memorable legacy of political resistance and leftist thought and practice. While on its own, it carved a space for itself for nuanced socio-political discourses under rather precarious and oppressive political climates, the periodical and its associated members were also part of a much larger social and political movement that unequivocally strived to ensure press freedom and, more broadly, the Pakistani people’s agency to be critical of those who govern them, be they democratically elected or authoritarian regimes.

Al-Fatah was not a stand-alone force against much larger stifling regimes and governments. Other publications and organizations, such as its contemporary, Musawat, and the PFUJ sought to intricately weave their leftist rationales and journalistic prowess to become a force of mobilization against censorship and draconian policies which military rule imposed upon the nation state. More than just a leftist publication, Al-Fatah served to counter anti-democratic practices, and worked towards redirecting the political landscape that guaranteed freedom of thought and expression. In doing so, not only did Al-Fatah’s contributors simply pen down their voices against governments that deliberately sought to silence critical thought, but they actively resisted, without fear, the perpetrators by collaborating with like-minded contemporaries who formed a large, progressive network. In doing so, these individuals constructed a legacy of resistance which Pakistan needed to preserve democracy and accountability in an increasingly unstable socio-political climate.

- Mir, Ali Husain and Raza Mir, Anthems of Resistance: A Celebration of Progressive Urdu Poetry. Roli Books Private Limited, 2006.→